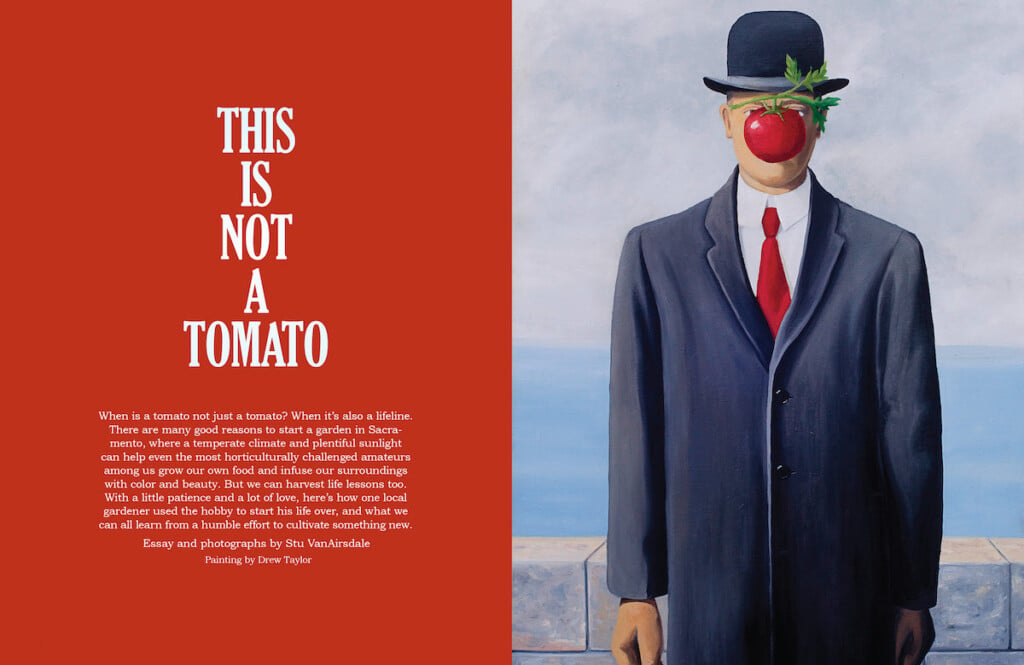

This Is Not a Tomato

When is a tomato not just a tomato? When it’s also a lifeline. There are many good reasons to start a garden in Sacramento, where a temperate climate and plentiful sunlight can help even the most horticulturally challenged amateurs among us grow our own food and infuse our surroundings with color and beauty. But we can harvest life lessons too. With a little patience and a lot of love, here’s how one local gardener used the hobby to start his life over, and what we can all learn from a humble effort to cultivate something new.

My first place in midtown Sacramento was a triplex unit on 17th Street, nestled against Uptown Alley. It was a dump—a little one-bedroom unit with a misfiring wall furnace and mid-century kitchen appliances that looked better than they cooked. Whatever. It was an address in Sacramento, and it was stable. I’d needed both upon my return to my hometown after nine years living and working in New York City. This was late 2013, and I was many things. A native son, a prodigal son, an alcoholic, barely solvent, starting over. I was also home. That’s what mattered.

My unit had a back door that opened into a tiny side yard. Next to the back porch, a sun-bleached tree stump lay corpse-like in a tangle of weeds. Upon moving in, I took one look at the mess and thought, “Cool, a garden.” My parents, who belong to the UC Master Gardeners of Sacramento County program, came by not long after and had a look for themselves.

“This would be a great garden,” my mom said.

“It already is,” I said. “Isn’t it?”

“Well, you pull these weeds, and…” Mom swiveled and pivoted, observing the thicket of groundsel and dandelions like a barber sizing up a Sasquatch. “You could do a lot back here.”

My dad nodded. “You want some tomato plants?” he asked.

“I dunno,” I replied. At that point in my life and experience, green was green. Weeds were as worthy of growth as any plant, weren’t they? After all, isn’t our state flower, the California poppy, considered a weed in certain parts of the world? What could I want with tomatoes or flowers, cultivated with purpose and structure? How would I even keep plants alive, with all their watering and… needs? Especially when all I really wanted to do after work was drink. What about my needs?

Then again, I was many things. Curious was another one of them.

By the following spring, in March 2014, I had filled two green waste bins with weeds, and had six tomato plants in the ground. My parents had also contributed dianthus, cosmos and zinnia flowers to attract bees and other pollinators to get the tomatoes going. I still had no idea about any of this. I was merely following my folks’ directions. My instincts were busy elsewhere: Around the same time, on March 24, I quit drinking. The previous night, after downing bourbon and beer, I had nodded off in the middle of cooking dinner on my crappy stove, nearly setting the apartment ablaze.

I was in bad shape, and I needed to change. Burning my home down would certainly have been one way to accomplish that. But the far more sustainable option for change was literally taking root outside my door, and I wanted to see what would happen. I was determined to figure out how to grow things in Sacramento—including, despite all odds, myself.

The essay’s author, Stu VanAirsdale, pictured at his former garden in East Sacramento on Jan. 26, 2024

In need of a healthy and constructive hobby, gardening was a timely solution hiding in plain sight. It wound up being just the right degree of accessible, challenging and rewarding: Those aromatic, emerald-green tomato seedlings soon blossomed into more produce than I could eat.

Later attempts to grow food taught me humility: In 2020, having since moved to East Sacramento, I had three pepper plants that yielded exactly one—one!—small yellow bell pepper between them. (I never deduced why.) My gardens and I have battled valley heat. I’ve fended off pests, from snails to squirrels. I’ve mourned plants I’d thought were invincible. I’ve also glowed with pride as garden experiments paid off for years to come, like the time I salvaged an overwatered $5 azalea I found all but dead and abandoned on a Lowe’s clearance rack. (The plant now bursts with big pink flowers every spring.) That’s the beauty of gardening: It’s your story. One plant, one season, one setback, one triumph at a time, you make your garden your own.

This March, I will be 10 years sober. I’ll also continue the process of starting over in Sacramento (again) after some time away. I’m renting a corner duplex in East Sacramento with virtually no plants or garden to speak of. I’ll make this one my own too. Spring is the time to do it, especially if you want to grow food. If you’ve ever needed a new beginning of your own, consider joining me. Here’s how, and—equally important—here’s why.

A Living, Breathing Personal Expression

In the abstract, the promise of a garden is an expression of hope and vitality as exuberant as any piece of writing or art or music—maybe more so. What other hobby carries the breadth of species and life and color and choice found in gardening? It’s also one of the only personal expressions that interacts with nature—both Mother Nature and our own perhaps equally unknowable nature. The process of identifying and acquiring the right plants for the right space requires an inside-out examination of terra incognita: What plants may thrive with the light and water and area we have available? How might we thrive among these plants, if at all?

More practically speaking, once we’ve assessed all of the above and really want to make a space ours, plants go a very long way. Sure, we can paint a residence or remodel it or refurnish it. Or we can surround ourselves with the most robust and creative garden we can afford. Even planting a few low-maintenance perennials like rhododendrons (good for shade) or lantanas (good for sun) that we can nurture and grow year to year is a worthwhile induction into plant parenting.

Just be advised: It will take several seasons to see and feel and experience the green bounty that the work yields. It took two summers for me just to prepare my most recent garden, scraping away a few hundred square feet of dreary lawn and a “hellstrip” (the patch of land separating a sidewalk from the street) in front of my previous residence in East Sacramento. But this waiting is part of the fun. Whether it’s six tomato plants and some flowers replacing my narrow thicket of weeds in midtown, or dozens of drought-tolerant salvias and a truckload of mulch that replaced my old lawns, neither nature nor I can rush the other. Just do your part by researching the right plant for you and watering when necessary. (I’ll get to that.) From there, the garden will speak for itself.

Putting In The (Dirty) Work

Notwithstanding my lifelong affection for the Sacramento Kings, I’m not a masochist. I don’t have an unusually high tolerance for pain. However, I love throwing on my Dickies coveralls and heading out for the gritty physical labor of working in the garden. Whether it’s the routine early morning watering made necessary by the summer heat, or the long days of digging and weeding and otherwise laboring ahead of my fall plantings, nothing rewards like the feeling—however sore—of a yard job well done.

I love amending my house’s imperfect clay soil with compost and earthworm castings to prepare new plants for their happiest lives. I love lifting and moving heavy potted trees and cloth containers of tomatoes until they’re in just the right spot. I love pushing wheelbarrows full of wood mulch and spilling the wood chips onto the ground and spreading them evenly around plants to help soil retain water and stay cool. I loved being in my old backyard and pruning the old Meyer lemon tree (whose thorns wounded me every time) and my newer anisodontea plant, which my mother bought me as a tiny green shrub in 2020 and which has since grown taller than me, exploding with leafy stems and pink blooms every spring.

I know this isn’t for everybody. You know that famous phrase typically associated with trauma, “The body keeps the score”? I won’t lie: The older I get, and the bigger and more involved my garden, that score is increasingly lopsided. I do understand why some people may opt to outsource this work to garden professionals. But I learned in those early days with the tomatoes that the simple analog physicality of basic gardening is one of the most satisfying parts of the whole endeavor. Try to do whatever you can yourself. The trade-off is a garden—your garden—that will yield pleasure for months and years to come.

Photos of the author’s garden of native plants in October 2021, both before and after planting and mulching

Common Ground

Ten years ago this spring, when I needed that constructive distraction, my parents helped me start a basic garden with tomatoes and flowers. Ever since, as personal and political differences occasionally strained our relationship, we could always talk about our gardens. We could discuss for hours my mom’s tips for propagating or dividing plants (in other words, turning one existing plant into multiple new ones) or my dad’s experience cultivating fruit trees (he grows sweet, juicy mandarins and pluots—a combination of plums and apricots). In an era miserably short on sources of comity, civility and compromise, gardening is blissfully apolitical. Soil doesn’t watch cable news. Roses don’t vote.

This connection makes intuitive sense with neighbors too, whom I’ve spent countless hours talking to about everything from how to find free garden goodies on Craigslist to the scourge of snails eating our herbs. Not all Sacramentans have the privilege of a few square yards of bare earth at home or access to the funds and plants or even the plentiful sunlight a garden requires. (A city of trees also means a city of shade.) This makes our region’s community gardens all the more important to develop common ground—literally and figuratively—with those around us. These spots are usually accessible on foot or by bike, offering affordable garden plots and on-site compost bins. They’re also hubs of creativity, color and wonder. For instance, I might wonder aloud to a fellow gardener what wizardry they deployed to grow so much healthy squash or what they do with so many peas. (Answer: Eat what you want, and give the rest away.)

I know it may sound corny to extol peace, love and unity as a byproduct of gardening. And to be clear, gardening is not a panacea. Weirdos and jerks lurk everywhere. But the inherent labor and humility of gardening tend to make it a self-selecting pastime for big-hearted folks of different backgrounds, generations and experiences who convene in one place around one interest. We can help each other, share ideas, revel in successes and commiserate over failures—often without even thinking about our divergent philosophies and persuasions. We’re all going to be on the brink in 2024. We might as well garden there.

Grow Your Own Therapy

If the physical toil and toll of gardening scare you off, consider the emotional upside. There is a meditative quality to many of the tasks a garden requires, with a singular type of emotional satisfaction and restoration as its payoff. Granted, I’ve heard that some folks achieve this sort of emotional “zone” by running, but I am not about to start running. (Unless you count running to shoo away a squirrel digging through a flower bed. Other than that, no way.)

Instead, I happily sink into the tedium of weeding—one of the least conventionally “fun” but most effectively mind-clearing exercises a person can perform. You can find much-needed focus in such tasks as digging holes or amending soil or watering or delicately trimming the roots on that potted cypress you love. In my new residence, I take periodic breaks to wander around the yard and daydream about what should go where when spring arrives. Even if I don’t plant half (or any) of what I have in mind, there is therapeutic value in imagination.

For the record, gardening and yard work are not substitutes for clinical therapy or medication. I’ve found, however, that they are highly effective complements to such treatments. I got sober in a garden 10 years ago. After a bad breakup in 2020, I found succor in the creative labors of planning and planting a whole new drought-tolerant garden in the front yard of the house I once shared with my ex. When life is hard—which is to say, every freaking day—you can’t discount the value of a little garden perspective to help the cruel world and its challenges fall away.

Trial and Error—And Success

Sometimes, though, the garden is the challenge. Despite your best efforts to sustain it, a plant withers and dies. A tree struggles to take root and grow. That bounty of peppers or squash or tomatoes you anticipated never materializes. The erstwhile Eden of your spring garden deteriorates into a crispy brown hellscape of broken dreams. What then?

Trust me: It’s fine. The process of weathering the triumphs and tribulations of a garden—especially when trying to grow food, which can be super humbling—is one of the most satisfying parts of the whole hobby. Would you believe that ever since that first year I was blessed with a bumper crop of tomatoes on 17th Street—more than I could possibly consume myself, no matter how many salads or salsas or sauces I made—I haven’t managed more than a few baskets of marble-sized Sun Golds and red grape tomatoes each year? It’s pathetic.

Like every garden problem, though, it has a solution. Or at least a diagnosis: In my case, the trees on my former tiny East Sacramento lot prevented the requisite eight hours of daily sunlight from reaching the tomato plants. The following year, I tried growing them in pots so I could move them into light as needed, but the extreme summer heat basically baked the roots in their containers, stunting the plants. They also needed more air circulating through the crowded, leafy stems. By the time I figured all this out, it was time for me to move again. At least the salvias and my Japanese maple in the front yard were well established and happy. You win some, you lose some.

Eventually, little garden lessons like these accrue to a sort of user manual for life. The longer you spend attempting to figure things out in a garden, and the closer you get to solving a particularly difficult problem, the more you realize why we do anything difficult at all. Gardening doesn’t give you a Grand Reason to “go on,” so to speak. It just grounds you when you want to stop. It gives you reasons to prove yourself—to yourself. For me, that meant a reason to give sobriety another chance after the first few tries didn’t stick. It meant a reason to confer and problem-solve with my parents, however awkward it could be. It meant a reason to seek restoration and love after heartbreak, however bad it felt and however long it took.

And this spring, it means a reason to plant more tomatoes—that deceptively easy crop I have botched for years—after so much trouble and frustration. I remain many things,including an optimist. My new place has the right light for them, with just one towering sycamore shading the corner. The backyard has room for a raised garden bed that I can build and maintain inexpensively. I want the bright smell of the vines and sunny yellow of the blossoms. I want the bees and butterflies and hummingbirds that orbit a garden. I want the harvest of undulating heirlooms and elongated romas and sleek black cherry tomatoes that came through for me a decade ago. I want the joy and reassurance that accompany getting it right. At least I hope I get it right. If not, so what? There’s always next year.

PRIMROSE PATHS

Not sure how or where to start with a garden of your own? Consider these five tips to get growing in no time.

Ask the green thumbs. Staffers at local garden stores like green acres carry deep knowledge about everything from seeds to irrigation. Members of volunteer organizations (including the UC Master gardener programs found in counties around the region) can answer your questions online or sometimes even in person. No question is too elementary, and they are always more than happy to help rookies. After all, they were once where you are.

Right plant, right place. Identifying the right plants for the right places will save you lots of time, heartache and money. Rhododendrons and hydrangeas, for example, are particularly good for yards with dappled light or shade. you wouldn’t want to put either of those in blasting sun, where they’ll burn to a crisp (especially in Sacramento). Hot, dry conditions might instead call for planting native salvias or succulents, both of which love sun and require relatively little water once established.

Consider raised beds. Shrubs, bushes and trees generally want to be in the ground, where their roots have room to expand and draw nutrients from our region’s excellent terrain. But food plants are pickier about soil quality and placement. Most garden or home improvement stores sell easy-to-assemble kits for “raised beds”—small plant bed enclosures made of wood, metal or dense plastic, which you can fill with soil and other organic materials calibrated perfectly for your seasonal harvest.

Don’t overwater. One of the toughest lessons for new gardeners to learn comes down to one word: drainage. A plant’s roots can drown if oversaturated or otherwise exposed to too much water. You can overthink this, so suffice it to say: Whether it’s in the ground or a raised bed or a pot, stick your finger into the soil around the base of any plant before you water it. If the soil is damp—even just a little—don’t water the plant. Now you know!

Know your limitations. A garden is what you make it, and you’re likelier to keep at it if you make it easy. If you’re garden-curious and untested, you probably shouldn’t plant a small farm that you have to maintain, fertilize, cultivate and troubleshoot indefinitely. Instead, envision what you want for yourself and cut it by at least half. Then cut that by half, and see what happens.

You Might Also Like

Where the Sidewalk Blooms – Bringing wildflowers to our concrete jungle

The City of Trees: A Love Letter – Our deep dive into Sacramento’s urban forest

Q&A with Jessica Sanders, Executive Director of the Sacramento Tree Foundation