Where She Was From

Sacramento native Joan Didion, who was one of America’s greatest writers, passed away on Dec. 23, 2021, at the age of 87. We spoke with the literary giant 10 years earlier, as she reflected on the deaths of her husband and only child, and her memories of growing up in River City.

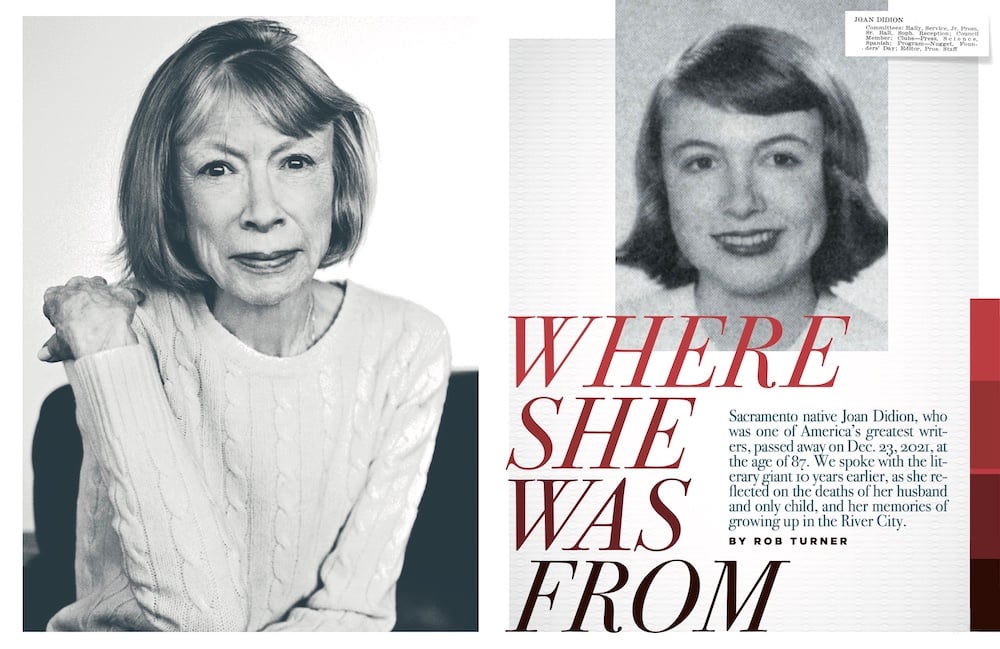

Joan Didion left Sacramento after graduating from McClatchy High in 1952, but in both her works and thoughts, the city remained a frequent companion.

From her first book, 1963’s Run River to 1979’s The White Album, 2003’s Where I Was From and what turned out to be her final original work, 2011’s Blue Nights, the city and her relationship with it was a recurring plot point. She spent considerable time ruminating on her hometown, as well as articulating the ways in which it defined her.

This is, after all, where she was born (on Dec. 5, 1934, at Mercy General Hospital on J Street), raised and educated, and where she published her first words, writing for the society desk of The Sacramento Union as a teenager. It’s where she first learned to swim, drive and dance. It’s where she fell in love with our rivers and dreamed of working at the State Fair. When she moved to New York to work for Vogue in her early 20s, she missed her hometown terribly.

In times of great distress, it was also the place to which she sometimes escaped, in her mind, to feel safe. And in her later years, emotional distress was a too-familiar presence for Didion. Blue Nights was about the 2005 death of Quintana Roo, her adopted child with the writer John Gregory Dunne. Named for a city in Mexico that Didion and her husband liked the sound of, her then 39-year-old daughter died of a series of illnesses that began with pneumonia and developed into septic shock and ultimately acute pancreatitis.

Dunne himself died at the couple’s dinner table in 2003, and the aftermath of that loss served as the basis of her previous book, The Year of Magical Thinking, which won the 2005 National Book Award for nonfiction.

After wrestling with and writing about the subject of death on and off for nearly a decade, she hoped that Blue Nights would be the last in a series of painful chapters.

This interview was conducted in October 2011.

First, I’m so sorry for both of your losses. With the new book, you must hear that a lot these days, even though it’s now many years after the fact.

Well, it doesn’t seem like so many years after the fact. After John died, I was startled to realize that after three years or five years, I still thought of it as yesterday.

In Blue Nights you wrote that you felt like writing does not come as easily now. You cite frailty, but you’re writing about a painful and personal subject.

Yeah, I don’t think that was it so much. Because actually, the last book, the book before this one, Magical Thinking, came rather easily. And that was equally personal. I think I just reached a point where I didn’t like writing.

So it was harder to write?

It was. I think it was that at that moment I did not feel like writing a book. I seriously considered not finishing it.

What kept you going?

The sheer knowledge that I had to do it, that I had to do it or I was going to live with not doing it forever. I did not intend to do this [kind of book]. I intended to write a book about people and their children, people’s attitudes toward having children, [something] much less personal with more research. And then, at some point, that Blue Nights image came to me, and then the title, and then the whole thing seemed more plausible and possible. But it definitely wasn’t a researched book about people and their children anymore. It was clearly what it was meant to be all along, which was about me and my child.

Was it cathartic for you?

No, I didn’t think it was cathartic. Cathartic is a terrible word. I thought it was cathartic in the sense that it would rid me of something, yes. But it wouldn’t make it go away. Cathartic, when we use that word, usually sounds as if the thing we are trying to be cathartic about will go away, but it doesn’t.

So perhaps it helped you process Quintana’s death?

It helped me process it. It doesn’t help you cope with it, it helps you process it. It makes it stop surprising you.

So is that what ultimately happened with both books?

That was the ultimate effect with Magical Thinking. I don’t know what the ultimate effect of this one will be. I’m through with the book, but I’m not through processing it.

From left: Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo, as a young girl; Didion, left, working on the McClatchy High School newspaper in 1952; the author’s photo that ran on the back cover of her 1970 book Play It As It Lays (Courtesy of Knopf; Courtesy of McClatchy High; Newscom/Julian Wasser/Zuma Press)

At one point in the book you write that “memories are what you no longer want to remember.” Once the book is done and you’ve faced those memories, does it allow you to move on?

Yes, I think so. I think it did, to some extent, with Magical Thinking. The image I always have in my mind is a snake. A snake doesn’t hurt you if you know it’s there. It’s not going to bite you if you keep it in your eyeline all of the time. So, in a way, this is keeping the snake in my eyeline.

In Blue Nights, you talk about how protective you were of Quintana and how growing up in Sacramento, you and your brother were allowed to “invent your own lives.” You wrote about driving to Lake Tahoe at age 15 and attempting some risky maneuvers rafting on the American River. Were you more protective of her in part as a reaction to how you were raised?

No, I think I was more protective because we just all became more protective of our children as a society. I mean, when you see children as they are being raised right now, you must be struck by how much more protected they seem to be than you were yourself. Not because there are more dangers, but because there are more perceived dangers. Or maybe there are more dangers, but I don’t see how there could have been more dangers [now] than there actually were when I was a child. I mean, people were always getting killed. I think parents just have a different attitude toward raising children. When I thought of myself as too protective, I didn’t understand that there was no way around it. I had to be the person to overprotect, because I was it.

Did the fact that she was adopted make you more protective?

Totally. Yes, because she had been given to me out of the blue, you know.

You write about all the difficulties surrounding the fact that she was adopted. Are there things that are specific to adoption that you would do differently?

No. I mean, it would be easy for me to say I wouldn’t do it, but I would do it—I’d do it in a flash. Nobody was so lucky as I was, to have a baby handed to me in that way. So definitely I would do it again.

You often brought Quintana to Sacramento to visit family, and in Where I Was From, you write about how when she was 5 or 6, you took her to Old Sacramento where your father’s great-grandfather owned a saloon on Front Street.

It was when there was Second Street and nothing beyond that. The name of it, I think, was Didion’s. But this was in another century, so it didn’t exist [when we went there].

You wrote that on that day in Old Sacramento, you stopped yourself from telling Quintana about his saloon because she was not truly connected to him by blood, although she is connected through you.

I counted her as connected. I had always counted her as connected to me, but then on that particular day that we went to lunch downtown, I realized that she really had a choice in this matter.

And she already knew then that she was adopted?

Oh, totally. She knew the word before she was verbal.

Was there anything from your childhood in Sacramento that you wanted to share with her?

I wanted to take her onto the rivers. I learned to swim in the Sacramento River, and the American. I spent a lot of time on the rivers, swimming and rafting and just doing stuff, and I thought that would be something I wanted her to do. But I’m not sure we ever did that, because by the time she was a strong enough swimmer it seemed easier to go to somebody’s pool.

In Magical Thinking, you wrote about having a panic attack while covering the Democratic National Convention in Boston. You were desperately trying to get your mind off John and Quintana and you did that by focusing on your high school dances in Sacramento at Christmastime.

Yeah, it just popped into my head as something safe.

You also mentioned focusing on the river and the levees. Was there anywhere in particular you went?

There were different places. One place was out where you start up the Garden Highway, and on the riverside, quite soon, there was a place where you could keep a boat if you had a boat. There was a restaurant. Then there were other places on the American, too. I would have to say the rivers are my strongest memory of what the city was to me. They were just infinitely interesting to me. I mean, all of that moving water. I was crazy about the rivers.

From left: Didion’s childhood home on 22nd Street in Sacramento; the cover of Blue Nights; Didion and husband John Gregory Dunne attending the Oscar de la Renta show in 2002, a year before Dunne died (Photo by Marc Thomas Kallweit; Courtesy of Knopf; Newscom/Rose Hartman/Zuma Press.)

Have you been back to Sacramento recently?

Not since my mother and father died, which was in the ’90s. I think that was the last time. My brother lives in Carmel and Palm Desert.

You write a lot about the houses that you had lived in with John and Quintana. Do you remember much about your old home in Sacramento on 22nd Street?

2000 22nd Street. One of my aunts had been living there and she decided to sell it [in 2007]. It was a great house. It was an odd house for Sacramento in that it was not Victorian or Edwardian. It was a slightly later date. And the proportions were a little different. Our first house was on U Street, and then after [World War II], we moved to what was then the country basically. It was Carmichael.

That’s when you went to Arden School, which used to be in the middle of fields. I don’t know if you know, but that’s down the street from where the first Tower Records was.

I remember the first Tower Records. I thought the first Tower Records was on Y Street.

Y Street is called Broadway now, and yes, that’s what most people think because Russ Solomon used to sell records out of his father’s pharmacy next to the Tower Theatre.

That’s right. There was something else that started in Sacramento. It was a pizza place.

Shakey’s?

Yes, Shakey’s.

And did you ever used to go to Vic’s for ice cream?

Oh yeah, of course. Vic’s was where we used to go when I was in California Junior High School [in Land Park, which is now California Middle School].

You also asked your father to get you a job at the State Fair.

I wanted a job at the State Fair, but my father would never make the call [on my behalf], so I never got one. Everyone wanted a job at the State Fair. That was the place to be. There was a lot of stuff that I liked about it. It was the fireworks, the county exhibits, the animals. I liked going to the barns. I took Quintana through the barns with the animals. I was pushing her in one of those pushcarts, and she was close to the ground, so all she could do was smell the animals—it was not a good experience for her.

What did you cover for The Sacramento Union in high school?

I was working at the society desk. I did weddings. I didn’t cover weddings, I just wrote about them. I wouldn’t call that reporting. On the society desk at The Sacramento Union, like any relatively small newspaper then, people wanted reports of their upcoming weddings in the paper the weekend of the wedding. And so they would send you accounts of what the bridesmaids were going to wear and stuff like that, and you would write it up.

Didion with Sacramento writer William T. Vollmann in New York on the night in 2005 that they each won the National Book Award, she for nonfiction, he for fiction. The ceremony took place three months after Quintana Roo died. (Henny Ray Abrams/AP Photo)

When you won the National Book Award for nonfiction for Magical Thinking in 2005, it was the same year William T. Vollmann won for it for fiction, and the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that “for a couple of hours Wednesday night, the literary center of the nation shifted to Sacramento.” Did you know that Vollmann lives here?

No! I didn’t know until this minute. Amazing, truly amazing. I met him that night. That is the only time that I have met him. I was only anxious to get out of that crowd. It was in a hotel—the Marriott on 45th Street [in New York]—full of hurtling elevators, and I was so dizzy from the elevators hurtling around and the lights flashing, that all I could think of was getting out of the Marriott.

Given the subjects of your last two books, you’ve been writing a lot about death. Has that forced you to think more about your own death? Are you more afraid of it now?

No, I’m not more afraid of it. I don’t think I was afraid of it to begin with. But it’s not something you would really want to spend too much time thinking about. I hope I will change the subject of my next book.

Do you already know what your next book will be about?

I haven’t got any idea. The one thing that I know about it is that I do want it to be another subject.

Notes From a Native Daughter

Run River (1963)

Martha McClellan was not yet seventeen, a freshman come fall at the University of California at Davis. When Lily’s mother, on the behalf of the Pi Beta Phi Alumnae Club, had urged Martha to enroll at Berkeley and participate in rushing, Martha had told her that it was necessary that she go to Davis, which was mainly an agricultural station, because her father wanted her to marry a rich rancher. And as a matter of fact so did she.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968)

I remember swimming (albeit nervously, for I was a nervous child, afraid of sinkholes and afraid of snakes, and perhaps that was the beginning of my error) the same rivers we had swum for a century: the Sacramento, so rich with silt that we could barely see our hands a few inches beneath the surface; the American, running clean and fast with melted Sierra snow until July, when it would slow down, and rattlesnakes would sun themselves on its newly exposed rocks.

Later, when I was living in New York, I would make the trip back to Sacramento four and five times a year (the more comfortable the flight, the more obscurely miserable I would be, for it weighs heavily upon my mind that we could perhaps not make it by wagon), trying to prove that I had not meant to leave at all, because in at least one respect California—the California we are talking about—resembles Eden: It is assumed that those who absent themselves from its blessings have been banished, exiled by some perversity of heart. Did not the Donner-Reed Party, after all, eat its own dead to reach Sacramento?

The White Album (1979)

I replay a morning when I was seventeen years old and caught, in a military-surplus life raft, in the construction of the Nimbus Afterbay Dam on the American River near Sacramento. I remember that at the moment it happened I was trying to open a tin of anchovies with capers. I recall the raft spinning into the narrow chute through which the river had been temporarily diverted. I recall being deliriously happy.

I have difficulty now imagining a childhood in which a man named Jere Strizek, the developer of Town and Country Village outside Sacramento (143,000 square feet gross feet area, 68 stores, 1000 parking spaces, the Urban Land lnstitute’s “prototype for centers using heavy timber and tile construction for informality”) could materialize as a role model, but I had such a childhood, just after World War II, in Sacramento. I never met or even saw Jere Strizek, but at the age of 12 I imagined him a kind of frontiersman, a romantic and revolutionary spirit.

Where I Was From (2003)

[My mother] thought of herself as an Episcopalian, as her mother had been. She was married at Trinity Episcopal Pro-Cathedral in Sacramento [at 2620 Capitol Avenue]. She had me christened there.

[My father] supported my mother and me during the Depression by playing poker with older and more settled acquaintances at the Sutter Club, a men’s club in Sacramento to which he did not belong.

The Year Of Magical Thinking (2005)