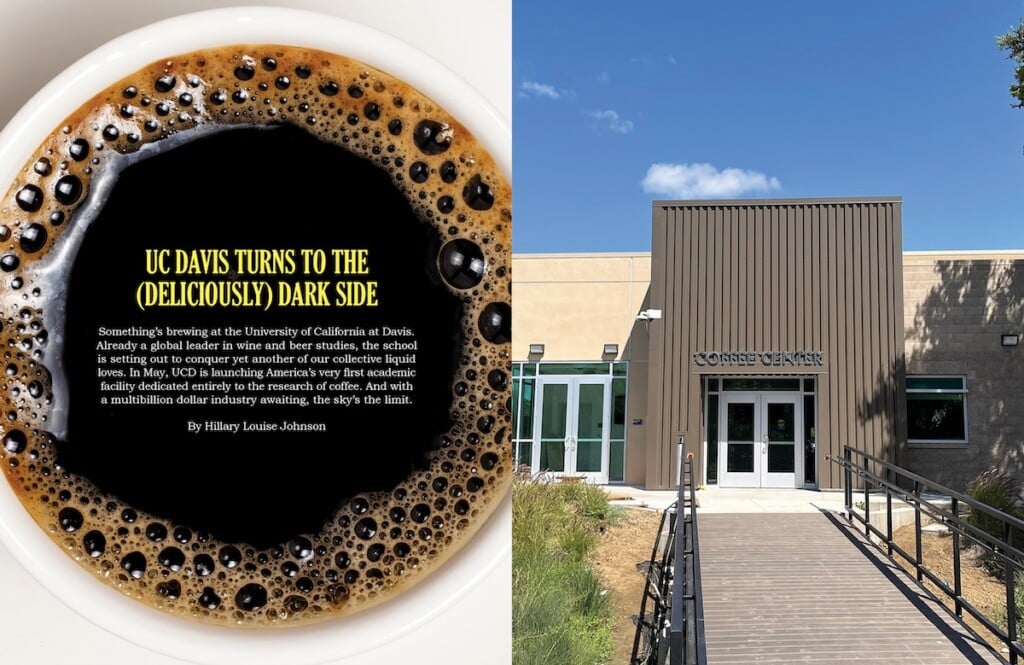

UC Davis Turns to the (Deliciously) Dark Side

Something’s brewing at the University of California at Davis. Already a global leader in wine and beer studies, the school is setting out to conquer yet another of our collective liquid loves. In May, UCD launched America’s very first academic facility dedicated entirely to the research of coffee. And with a multibillion dollar industry awaiting, the sky’s the limit.

Next time you stroll or roll through the UC Davis Arboretum, you may find yourself pausing in the South American garden to breathe in the air. What is that luscious, roasty aroma redolent of chocolate, caramel, nuts and maybe… marzipan? And where is it coming from? If you follow your nose across Putah Creek—picture yourself levitating and wafting dreamily through the air, like Bugs Bunny floating after a carrot—you’ll find yourself at the footsteps of the university’s shiny new Coffee Center, where, on a warm spring day, 6,000 square feet of bustling laboratories for roasting, brewing and tasting the world’s most craveable commodity are flung open to the campus via rows of glass-faced garage doors that give the entire facility an indoor-outdoor feel.

Surrounded by gardens, with an industrial-chic design palette, the UC Davis Coffee Center—which hosted its grand opening on May 3—has the vibe of a cosmopolitan urban cafe. But while you can buy a bag of beans, you can’t order a cup of coffee here, not unless you’re a study subject in the tasting lab. And the “baristas” are all wearing lab coats—some of them on their way to a Ph.D. in food science or chemical engineering, and eventual careers in a galloping global coffee industry that in 2022 saw more than $340 billion in economic impact in the United States alone. Yet this is the first academic center in the country dedicated to the scientific study of the entire coffee supply chain, and we wouldn’t even be having this conversation were it not for another serendipitous conversation between two colleagues drinking coffee in a hallway.

In addition to being a hub of learning, the new UC Davis coffee center will serve as both an event center and a place for students, faculty and the community to congregate and commune. (Rendering courtesy of UC Davis)

It happened in 2012, when chemical engineering professors William Ristenpart and Tonya Kuhl were brainstorming ideas for lab experiments. “If you can do hands-on demonstrations and experiments,” Kuhl says, “it’s just way better for learning.” So she suggested they have students reverse engineer a drip coffee maker to deconstruct the process and all its variables, like time, temperature, concentration and rate of flow—enlivening the learning by letting it unfold in the context of something as familiar and beloved as everybody’s favorite study aid: coffee.

“And I thought,‘Oh my gosh, let’s do that,’ ” Ristenpart recalls. “ ‘But let’s make a whole class about coffee.’ ”

Excited by their “Eureka!” moment, they ended up creating both an advanced-level lab course and an elective called “The Design of Coffee.” “We’re basically using coffee to illustrate engineering principles in a friendly and approachable way,” Ristenpart says. “The last week of the course is an engineering design contest to make one liter of the best tasting coffee using the least amount of electrical energy—a classic engineering optimization problem.”

They expected 100 students to enroll. 350 signed up. Fast-forward to 2024, and “The Design of Coffee” is among the most popular electives on campus. More than 2,000 students a year sign up for the course—that’s a healthy percentage of 9,000-plus incoming undergrads, giving new meaning to the phrase “Joe College.”

This is how the Coffee Center was born—thanks to the awareness leveraged by the class, professors across disciplines began collaborating on coffee-themed research, and Kuhl and Ristenpart found themselves with a web page, if not a building yet. Meanwhile universities elsewhere have begun offering versions of the class, including University of San Diego; University of Colorado, Boulder; and Auburn University in Alabama. These all use a textbook Ristenpart and Kuhl have published, The Design of Coffee: An Engineering Approach, so it’s pretty clear where the first butterfly flapped its wings.

The Specialty Coffee Association, a global industry group based in Irvine, were early supporters, funding the nascent Coffee Center’s first research projects. Peter Giuliano, the organization’s chief research officer, laughs when I call him to ask about the relationship, then sighs happily, sounding a bit like an adult who just found out that Santa Claus is, in fact, real. “I can’t tell you the number of times I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if there was a UC Davis for coffee?’ ” he says. “I was thinking maybe someday some university somewhere in the world would embrace coffee as an academic pursuit the way UC Davis has pursued winemaking. Little did I know it would be UC Davis!”

The study of coffee, Giuliano thinks, can impact every field from science to sociology. “Just as soon as coffee came to Europe, the Enlightenment happened,” he observes—implying, perhaps, that we owe the foundations of our very civilization to the bean. “Coffee is legendarily under-researched,” he says. “There are a lot of mysteries.”

The center’s tasting room is a well-lighted, indoor-outdoor space where researchers and volunteer tasters will interact on the regular. It may look like a hip third-wave specialty coffee shop, but it’s designed to create the ultimate lab environment. (Rendering courtesy of UC Davis)

It’s no wonder the university quickly decided to wake up and smell what was brewing—in 2016, the then-dean of engineering Jennifer Curtis gave Ristenpart the green light to start fundraising for a dedicated building.

“As dean, lots of people come to you with different ideas for projects,” Curtis says. “This one was an easy yes. First, it addressed a knowledge gap: there was nothing out there, anywhere in the world, in coffee education. Second, the [Design of Coffee] course itself was the coolest thing at UC Davis, making science and engineering concepts relatable to all majors, not just science and engineering people. And third, the project leveraged our international reputation for beer and wine.”

The university’s Department of Viticulture and Enology, established in 1935, has over a dozen full-time faculty, as well as a Teaching and Research Winery, and shares the world-class Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science with the Department of Food Science and Technology. And the beer brewing program, started in 1958, is one of the oldest and most respected in the country.

“We want to do for coffee what UC Davis has done for wine and for beer,” Ristenpart says. The students and faculty were all in, now the only thing that remained was a place for the Coffee Center to hang its shingle.

There are still hard hats on the scene when Ristenpart rides up on his bicycle to give me a tour of the building that shares a parking lot with the Putah Creek Lodge event center, though there are enough finishes in place to clock the cool vibe. To a coffee lover, walking into this airy, aromatic Valhalla is like stepping into Willy Wonka’s candy factory, a museum and a house of worship all rolled into one—and the dramatic, cathedral-ceilinged laboratories reinforce that feeling.

The almost church-like verticality of the repurposed building—which previously housed a hydrogen fuel cell laboratory—is a legacy of its original design, but the effect is literally and figuratively uplifting, well-suited to its new focus on caffeinated consciousness-raising.

Chemical engineering faculty members William Ristenpart and Tonya Kuhl brewed up the idea for the university’s first coffee curriculum—which eventually led to the coffee center that they co-direct—over cups of coffee in a campus hallway. (Portrait by Andri Tambunan)

Lance Kutz—who oversaw the renovation as the former principal in charge at Perkins Eastman, the firm that designed and built out the center—got the inspirational vibe immediately. Kutz embraced budgetary challenges by envisioning the facility as akin to an edgy, warehouse art gallery, tearing out dropped tile ceilings but leaving the space’s industrial character intact. “The building’s interior is just very simplistic, clean and white,” he says. “Here the coffee gets to be the exhibit—it is the art.”

That dash of art-world chic is fitting for a place that aims to think outside the cup, with an eye toward issues like climate change and social justice. People in the coffee industry liken the humble bean to commodities like oil when describing its importance to developing nations. And it might be an apt comparison: According to the Fairtrade Foundation, 125 million people worldwide earn their livings in the coffee industry, while the oil and natural gas industry, though vastly more profitable, employs 32 million.

But Ristenpart is talking about more than just numbers. “If you think about it, one fuels our vehicles and one fuels our brains,” he says, hoisting the insulated mug he brought from home as he ushers me into the Cropster Corridor, named after a company that builds software for the coffee industry and has headquarters in Sacramento and Innsbruck, Austria. Each space in the building is named for a sponsor—think Peet’s, La Marzocco, Folgers, with smaller donors acknowledged within a graphic of a coffee tree in the sunny lobby that faces the arboretum.

Cropster’s main software product is a system for managing roasting profiles (recipes specifying parameters like time and temperature). And Devin Connolly, Cropster’s head of customer success—he helps roasters and farmers learn the software—was a student in the inaugural “Design of Coffee” class when it was offered campus-wide as an elective in 2014. “He sat in the front row taking notes the very first time I taught the class,” Ristenpart remembers.

When his old prof started raising money, Connolly really wanted to help out, but Cropster didn’t have the deep pockets to donate cash to fund a lab. What he could do instead was introduce his former professors to people he met at trade shows, like the Specialty Coffee Association’s president. “That’s really cool to me to see my alma mater, professor and industry that I love all connected,” Connolly says.

Through that connection, Ristenpart was put in touch with corporate partners for the project. “This is the Peet’s Roasting Lab,” Ristenpart says, leading the way into a room lined with duct work for three donated roasters from Probat, the German maker of high-end roasting equipment. Multiple, identical roasters will allow for controlled experiments, what scientists call “A/B testing,” in which multiple batches are processed simultaneously, changing only one variable at a time. These experiments will be conducted by the full-time Probat Roasting Fellow, who, along with all the lab’s researchers and students, will use Cropster’s donated software in their studies.

Ristenpart (right) and Timothy Styczynski, the coffee center’s head roaster, flank a new Probat roaster, donated by one of the facility’s many in-kind benefactors. (Photo by Andri Tambunan)

Next door is the La Marzocco Brewing and Espresso Laboratory, sponsored by the Italian manufacturer of top-end espresso machines and grinders. Four stations are plumbed and wired for espresso machines, along with over a dozen more for commercial drip coffee makers, grinders and pour-over stations. If there’s a way for hot water and beans to meet, it can happen here. Meanwhile across the hallway, the Toddy Innovations Lab for cold brew technology is named for the company that holds numerous patents for methods of brewing coffee that don’t use heat—said to produce particularly sweet and aromatic extractions.

On the other side of a pass-through window (the kind you’d see between a restaurant kitchen and a dining room) is the sensory and cupping lab, where a row of isolation booths wait for taste testers (the public may be able to join the tasting program or sign up for weekend workshops at some point). The booths look a little like voting booths, but smaller, each with a small countertop that orients its occupant toward a sliding panel just big enough to pass a cup through, illuminated by a dim red light. “The red lights are to minimize expectation bias,” Ristenpart says, “because if a cup looks very dark and strong, then you will perceive it as darker and stronger than it really is. So the idea is to have very little illumination.”

This is an area where coffee rivals wine in complexity: tasting. And that is the bailiwick of Jean-Xavier Guinard, professor of sensory science at UC Davis and Ristenpart and Kuhl’s third co-director of the Coffee Center. “As you know, there are established notions of what type of wine goes with what type of food,” he says. “There is such a range of coffees out there it begs the [same kind of] question.”

Guinard recently collaborated on a study of coffee and food pairings with local roastery Temple Coffee, which has several “Design of Coffee” grads among its employees, and a lot more who are educated customers at its downtown Davis shop. For the study, Temple donated the coffee and collaborated on the study design by bringing their anecdotal experiences from years of running cafes to help researchers narrow down test parameters. As a result, Temple will recommend a chocolatey coffee when you order a pastry—never one that’s fruity or acidic.

“I think [UC Davis] has had a big impact in the Sacramento specialty coffee community,” says Elise Jones, Temple’s director of education. “We just have so much access to state-of-the-art information, making sure we’re on par with what the international community is doing. It’s a really cool opportunity.”

Timothy Styczynski, the Coffee Center’s head roaster and founder of Marysville-based Bridge Coffee Co., is another good example of how the Coffee Center is already partnering with the local coffee community. Styczynski is a passion-driven, garage-band-style, self-described “micro roaster” (according to Roast Magazine, any company that produces less than 100,000 pounds annually qualifies as “micro”). He says his company’s name Bridge is about “connecting the coffee drinker to the coffee producer communities.” Styczynski has already advised on projects, including a new phone app released in April called RoastPic, which can measure and catalog things like roast level from a close-up photo of a tray of beans. The software uses AI similar to that used in facial recognition to analyze and track characteristics like color, size and texture to evaluate the beans.

This is important data, as roast level is to specialty coffee what the International Bitterness Units (IBU) is to the craft brewery business—that number that can steer you away from, or towards, a super dank IPA. Styczynski compares roast level to another matter of taste most of us can relate to: “I like smoked salmon, but I like the taste of salmon, so I don’t want to taste just smoke,” he says. “I don’t mind a lightly smoked coffee, but I still want to have the origin’s character come through. [RoastPic] will allow us to give a really accurate roast score, but it will be something very cost-effective and approachable for the small operators that don’t have thousands of dollars for a colorimeter.”

Who says you can’t reinvent the wheel? Attending the 2021 Specialty Coffee Expo in New Orleans, Jean-Xavier Guinard—a food science professor and co-director of the coffee center—stands in front of the Specialty Coffee Association’s reimagined flavor wheel that one of his graduate students helped create. (Courtesy of Jean-Xavier Guinard and UC Davis)

As for the center’s international reach, that was demonstrated quite early in its history. In 2016, Guinard supervised a graduate student, Molly Spencer, as she helped revamp the Specialty Coffee Association’s Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel, bringing to bear all of the research done since it first appeared in 1995, adding significantly to the vocabulary of flavors. Want to see where a cinnamon notefalls on the continuum? Right across from citric acid, according to the wheel. The result is a useful Rosetta Stone for describing roasts succinctly and elegantly—and consistently. Next time you pick up a bag of single-origin Costa Rica and read “notes of lemon zest, marzipan, nutmeg” on the label, that description isn’t just creative writing. It’s language that comes from, or is inspired by, combinations from the wheel. The 2016 version also happens to be a sexy, gorgeous graphic that has caught on with coffee enthusiasts around the world—you can even buy wall-art renditions of it on Etsy. “I travel far and wide,” Guinard says, “and to see that Flavor Wheel plastered on the walls of coffee shops in Bangkok and Madrid, it’s very exciting.”

Moving on with the tour, we pass through the green bean storage lab. After the coffee berry is picked, the red fruity portion is removed, leaving a green bean that must be kept fresh until it is roasted. The lab is set up with environmental chambers that can monitor temperature and humidity to determine optimum storage conditions—important for a commodity that can be shipped around the world in containers prior to roasting. We continue out to the garden space all these labs open onto, where a modernistic pergola of plasma-cut steel recreates the dappling effect of leaves below.

Back inside the center, things get serious: In the Folgers Chemical Analytics Lab, rows of equipment allow chemical engineers and food scientists to parse beans and brews at the molecular level through processes like mass spectroscopy, a method equally useful in diagnostics and forensics that can identify the exact molecular, even elemental, composition of any given sample of organic matter—lest you forget that this facility is far more than a garden of caffeinated delights.

The research that continues to snowball as it rolls out of the Coffee Center is impressive, and students aren’t the only ones on campus who are coffee-crazy. Already 50 faculty members are associated with the center—and not just from the hard sciences, but disciplines as diverse as law, economics, business and sociology.

“I get emails from people around the world asking, ‘Where do I sign up for a Ph.D. in Coffee Science?’ ” Ristenpart says. “But there’s no degree in coffee science—yet. I can easily dream up a core curriculum that is what a really educated coffee person should know. I’d like to grow the program into a highly respected master’s program in coffee, and it would be the first one in the United States.”

The process of forming a degree program, let alone a department, takes years. But some students, like Laudia Anokye-Bempah, aren’t waiting, and instead are putting together interdisciplinary degree programs of their own. Anokye-Bempah came to Davis from her native Ghana to study biological systems engineering, and soon fell in love with coffee, doing her master’s degree work on preserving green coffee beans during the long months of travel from their countries of origin.

Laudia Anokye-Bempah, a doctoral candidate in biological systems engineering, developed a passion for coffee studies at UC Davis and has already conducted important research on roasting. (Photo by Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis)

“I wasn’t a coffee drinker,” she says, even though Ghana does grow coffee as an export. “It’s funny, but these countries that produce a lot of coffee, they don’t drink it.” Changing that by creating local markets for consumption, she thinks, would bring economic benefits. “If producing countries learned how to roast coffee they’d be keeping more of the money, building their economy. It would be very useful.”

Now Anokye-Bempah is pursuing a Ph.D. in the same field, but with an eye toward quantifying the roasting process to create a tool for roasters worldwide to better plan and control their roasts. Having a global reach is on the center’s long-term agenda, and the prospects for growing a sustainably focused industry are good. Coffee farming is one of the last agricultural holdouts against the culturally and economically flattening influence of agribusiness: Anywhere between 60% and 70% of coffee is grown by family farmers, many too small to afford to seek organic or fair trade certification. The kind of scientific inquiry that can improve their productivity and efficiency could have a significant impact on developing world economies.

The tour ends out back of the building where a grove of redwoods surrounds a small but verdant lawn. Ristenpart gestures wide. “We have a nice Western exposure here,” he says, describing where he hopes to someday put a greenhouse, and a post-harvest processing station, so the center could grow its own experimental samples and really study coffee from sapling to sipping. “So then we’d have the whole thing,” he says, “from DNA of the seeds all the way to the psychology of how you perceive coffee in the cup.”

That is not, he emphasizes, part of the official plan—but sometimes caffeine dreams really do come true.