The Rise and Rise of Alex Honnold

Alex Honnold makes his ascent on the Eagle’s Way route of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park on June 4. (Photo by Max Whittaker)

His mother calls them “monstrously huge” hands.

Universally, it is agreed they are massive and preternaturally strong—the kind usually dubbed mitts or hams. The fingers are the size of ballpark franks swollen on a hot grill. They’re thick and round all the way to the nails. The tips are so strong that the topmost joints, which most people have trouble even bending on their own, can curl over and clamp down on the most minuscule protrusions, moving the entire 160 pounds of the long, lean body to which they are attached—fingertip pull-ups, if you will—often done in defiance of death while hanging thousands of feet above barren ground.

On the pads, the fingerprints are worn away from being jammed into cracks and pressed on ledges during years of rock climbing. What’s left has been ruthlessly, purposely eroded with a sanding block to prevent bulky calluses. These hands will never pick your pocket or fix your watch. It is difficult to conceive of them comfortably gripping a pen, and who knows what mayhem they wreak on texts. They are extremities that are both the product of the trials they have weathered and a testament to the physical prowess of their bearer. You would not want to thumb wrestle this guy.

These hands belong to climbing legend Alex Honnold, a 29-year-old Carmichael native who is considered the top free solo climber in the world—a niche of rock climbing that takes him thousands of feet into the air on some of the earth’s most precipitous peaks with no rope, no safety equipment, and no chance of survival if he falls. He claimed his place in the elite ranks of the sport in 2008 by mastering the Regular Northwest Face of Yosemite’s Half Dome that year, becoming the first person ever to climb the route this way.

Since then, he and his hands have adventured, with and without ropes, across the globe.

This year, Honnold did his fifth ice climb (using gear) by conquering the five-day Fitz Roy Traverse with fellow legend Tommy Caldwell in Patagonia, a never-before-done combination of routes up a series of seven peaks that crosses three miles of terrain and more than 13,000 feet of vertical gain. Before that, in January, he became the first person to free solo El Sendero Luminoso, scaling the 1,750-foot sheer Mexican rock face in just two hours. And this fall, he hopes to King Kong his way up the side of an urban peak—Taipei 101, a nearly 1,700-foot-tall skyscraper in Taiwan that was, until 2010, the tallest building in the world—on live TV.

Alex Honnold’s “monstrously huge” hands, whose fingerprints have been worn away from years of rock climbing (Photo by Max Whittaker)

He has also become a master of speed climbing, another tangent of the complex culture of the sport that challenges the small cadre of people who do it to see if they can reach the summit just a bit faster than the guys before—and yes, it is mostly men. Honnold owns about a dozen of these pace records in Yosemite, including one up the center of El Capitan (considered some of the most extreme “big wall” climbing in the world) called The Nose. Those hands took him up the 2,900-foot ascent in two hours and 23 minutes, an achievement that takes an average climber four to five days, while a crowd of spectators in the field below cheered and rang cow bells. He is a celebrity in the world of stone.

John Long, another celebrity of the sport who was, in 1975, a member of the first team to scale El Capitan’s “Nose” route in a single day and was one of the early pioneers of free solo climbing, says Honnold is “setting the bar” in adventure climbing and is “the most accomplished free soloer ever.”

But Taipei 101 would be an entirely different kind of coup—a televised spectacle that drives him from fringe sport notoriety to prime-time fame. It’s an idea that was inspired in part by Austrian BASE jumper Felix Baumgartner skydiving 24 miles to earth in 2012 for a stunt funded by energy drink maker Red Bull. Always searching for bold and singular adventures, Honnold began scouting for a man-made monument to scale. But there were not that many buildings interested in the scheme. “There’s a very short list,” he admits.

He went to Dubai and checked out the world’s tallest structure, Burj Khalifa, but found its futuristic architecture too daunting for his first televised exploit. Taipei 101, he says of its clean and simple design, is “super aesthetic,” a spire of blue-green glass and aluminum created from eight repeating square segments that angle slightly outwards, rising out of the dense city center with lonely grandeur. He climbed up to the top of the antenna while researching the possibility and dubbed it “pretty impressive.” While fame is far from Honnold’s goal, ascending the tower would be a drama for the masses that moves him from athlete to performer, an Evel Knievel for a new era of vicarious thrill seekers—a daredevil at the pinnacle of his game.

*******

Daybreak hasn’t yet reached the Yosemite Valley when Honnold arrives in the small hours before a warm June dawn. This early, the park is quiet and deserted as the deep black of a wilderness night breaks into purple shadow, although by breakfast the road will be clogged with buses, RVs and cars cruising for a view of the stately peaks and falls.

Parked in a blue ’80s VW van on the side of the road at the base of El Capitan, he and his climbing partner for the week, David Allfrey, are readying their gear to attack a route up El Cap called Eagle’s Way. The granite monolith, the largest in the world at 3,000 feet, has more than 100 established climbing paths up its faces, and Allfrey and Honnold are on a quest to complete seven of them in seven days. No one has done this before, but the idea has been floating around in the circle of speed climbers for years.

They’ve finished two complicated paths already—New Jersey Turnpike and Tangerine Trip, breaking the speed record on both by combining their talents. Allfrey is an aid climber—adept at pounding pitons and other gear into the rocks to create his own route, and hauling himself up with ropes and ladders when the face offers no grips. Honnold is the stronger free climber, able to lead the way when the natural surface provides its own path.

They are after another speed record today. Ammon McNeely and Brian McCray, top climbers and friends of Honnold and Allfrey, completed this route in nine hours and eight minutes in 2004, though regular climbers take about four days, hauling gear and sleeping on platforms pegged to the wall. Honnold is certain they can do better. “There are probably very few people who do exactly what we’re doing right now,” he says, describing the effort as a “game” more than a competitive sport. “I mean for me, this is more a test of fitness and mastery of skill than necessarily difficulty,” he says.

At the base of Eagle’s Way, where the climb turns from rocks and boulders to sheer vertical granite, the timer will start. There, after bounding leisurely up nearly 800 feet in 36 minutes on the approach, Honnold pulls out a map and scouts their first moves. He seems taller than his 5-foot-11 frame, lithe and built of pure muscle—the fit product of a vegetarian diet and hard training. Shaggy brown hair frames high, angular cheekbones and a solid jaw, a perfectly symmetrical face that’s earned him more than one “sexy” comment on the Internet.

But it’s his brown eyes that define him—huge, round, worthy of a Walter Keane painting. They mix intelligence with a wild blankness, like a feral creature somehow caught wandering in civilization. They’re the eyes of someone who knows that he thinks and feels differently than most people around him but doesn’t worry about what that means. He’s an iconoclast in a sport of nonconformists.

“This is one of the biggest, cleanest walls in the whole world,” he says, slipping off his regular shoes and jamming his bare feet into rubber-soled ones made for performance climbing, so tight and constraining they force his foot to arch like ballet slippers. They hurt to wear and he plans on switching back to his approach shoes when he’s not leading the climb—he and Allfrey will trade back and forth depending on the needed skills. “El Cap is maybe the best piece of rock in the world. I mean, it’s just so clean. It’s like perfect.”

Allfrey, a compact guy with long brown hair secured in an orange elastic band, a scruffy beard and easy smile, pulls on a pair of baseball gloves and white-framed sunglasses and checks his watch.

“Six thirty, exactly,” he says to Honnold, who’s looking up at the granite wall in the growing morning light. “I’m waiting for you to start climbing.”

“OK. On your mark, get set,” says Honnold jokingly. They’re going for speed, but in climbing, it’s a relative concept. Each move requires thought, technique and precision. What enables successful pace attempts isn’t only how fast the climbers move, but the skill and strategy of the players in this strange game.

“This is the thing,” says Honnold in his trademark self-deprecating way—“humble” is the word most often used to describe him, with “mellow” coming a close second. “It’s speed climbing but it’s going to be ultra fucking slow.”

“We realized yesterday that it’s like we’re the fastest of all the snails,” adds Allfrey.

“What I like about speed climbing is that it’s like perfection,” Honnold explained a few days earlier as he was prepping for the trip at his childhood home in Carmichael where his mom still lives, a tidy and spacious ranch house done up in browns and creams. “Like when we speed climb The Nose, we aren’t physically moving that fast. If you see video footage of it, you’re just kind of like, ‘Oh, it’s two dudes climbing.’ It looks totally normal, but all the transitions are flawlessly executed. Everything is done perfectly. All the gear placements are in the right place. Both people are just moving continuously at a steady pace for the entire mountain. It’s like a two-hour flow session.”

Honnold digs his thick fingers into the rock and starts up. Allfrey hits his timer. Climbers rely on honor for these records, trusting one another to play fair. Within a few minutes, Honnold is 100 feet up and not liking the conditions, which he reports down as “unpleasantly moist.” The rock is “wet and gross and covered with silverfish.”

A slow drizzle of a drought-season waterfall spills down about five feet to his right, a hummingbird darting in and out for a drink. Honnold is focused the other way, looking for holds that aren’t covered in slime. This first pitch, the climbing term for a single section of a route, is harder than expected because of the water. Allfrey realizes that his planning was based on an autumn climb when the rock was bone dry after the late summer heat. In rainy seasons, this route is covered by Horsetail Falls and even now, the rock is slick. “Yeah, maybe that was an oversight on my part,” he calls up, completely unfazed.

Then Allfrey asks if Honnold is “off,” meaning he’s secured the rope and moved on so Allfrey can begin. “Off enough,” yells Honnold, straddling two points with water running down between them as he clips the rope into an anchor and moves gracefully to a ledge so slim it almost appears he’s floating. “You’re off,” says Allfrey, tugging on the rope to test it before starting his ascent.

Honnold is moving fast. He starts to look smaller against the rock, an indistinct form in a red shirt and black pants moving steadily to the summit 1,800 feet up.

“God, the wall is like alive with silverfish,” Allfrey calls in a voice both disgusted and energized. “It’s so gross. They dive into your mouth and eyes. They pop off the wall like popcorn.” But he’s making progress despite the bugs.

He’s high enough up that when Honnold’s approach shoes are noticed sitting at the base, forgotten, it’s too late to come down. His feet are going to have to suffer.

*******

That kind of carelessness wouldn’t happen on one of Honnold’s free solos. When he ventures out with “just shoes and a chalk bag,” the latter used to keep his hands dry during ascents, he says it’s because he’s prepped hard. He practices with safety equipment multiple times first, even clearing the route of debris and loose rocks.

These “missions,” as he calls them, happen only a few times a year and are far more intensive than his blasé demeanor lets on. He would never try a major free solo without knowing every move mentally and physically—and he wouldn’t choose a climb that pushed his boundaries for its difficulty. That’s the trick of free soloing, he says—picking routes that are technically easy for him (despite the gut-dropping heights), like a jog around the track for a distance runner. With those constraints, he argues, unconvincingly, that free soloing is not as dangerous as it sounds.

“I never really had close calls climbing,” he claims earnestly, a hint of impatience creeping into his deep voice. “I think my biggest pet peeve is all the [talk of] daredevil stuff and risking death. I’m starting to feel like I have this canned response. The response is, ‘Everybody faces risk in their life to some degree. It’s just a matter of how you deal with those risks.’ I have a very narrow skill set, which I’ve practiced extensively. Within that, I feel quite comfortable.”

“Anyone who thinks Alex Honnold is a daredevil knows nothing. He’s a master,” adds Long. “I can’t imagine him ever getting hurt at it. Free soloing was invented for Alex.”

“This guy has basically no fear,” says John Robinson, 70, a retired engineer from Elk Grove who has climbed with Honnold for nearly a decade, starting when Honnold dropped out of UC Berkeley at age 19 after his father, Charles, an ESL teacher at American River College, unexpectedly died of a heart attack. “He just has a unique ability to stay focused and eliminate fear.”

In a rare admission of ability, Honnold agrees. “I’ve probably learned to handle things slightly better than average,” he concedes, adding that climbing with ropes has given him the experience and knowledge to handle most setbacks that come his way. Unexpected birds, hissing bats, falling rocks, storms—he’s climbed through them all.

“People are always like, ‘What happens if it rains? What happens if it’s windy? What happens if it …’ and I’m like, ‘Dude, I’m outdoors like 300 days a year doing exactly this,’ ” he argues. “It’s not like it’s never rained on me. You get wet. Next question.”

He illustrates his point with scorpions. “I remember being younger and being kind of afraid of spiders and little creepy-crawlies,” he says. “Or like small scorpions and stuff. I’ve actually found a lot of scorpions climbing because you pull a rock off and you’re like, ‘Oh, there’s a little scorpion.’ The initial instinct is just to whack at it with a piece of climbing gear until it falls off but then you’re like, ‘It’s not that big a deal,’ you know? Even if it stings you, it’s going to hurt quite a bit, but it’s not truly dangerous. You’re not going to die. You’re not going to necessarily fall off. You’re just going to be like, ‘Holy God, my arm.’ Now I can look at it and be like, ‘Even though that looks very scary and it’s potentially somewhat painful, it’s not true danger.’ It’s not like this is going to end me. So you can just kind of be like, ‘Deep breath; ignore the scorpion,’ and just work around it.”

Allfrey, who has partnered with Honnold many times, backs that, saying, “he mitigates and processes fear differently” than other climbers, but admits that there are things Honnold does that make him nervous. “There are perhaps times I am more scared climbing with Alex,” he says, “because his confidence level is greater and he can climb and do things other climbers can’t do.”

While Honnold is relaxed about the dangers he faces climbing, even with no gear, family and friends aren’t nearly as sanguine.

The would-be pro climber at age 9 with his sister Stasia in Long Island, New York, in 1994. (Photo courtesy of Alex Honnold)

“It freaks me out,” says his older sister Stasia Honnold, an environmental educator in Portland, of her brother’s free solos. “He doesn’t tell me he’s going to do stuff until after he’s done it and that’s fine. It does worry me for sure.”

His mom, Dierdre Wolownick, a French professor at American River College, adds that she considers free soloing a “horrible sport. It’s a horrible thing to do in terms of how safe you are,” she says.

Those in the climbing community are even more blunt. “Eventually if you keep doing this, there’s a good chance it’ll catch up with you,” says Tom Evans, a retired teacher and climber who now spends months every year photographing climbers in the Yosemite Valley as well as running a website called elcapreport.com that details what’s happening on the walls of the valley. “Everybody who knows him is worried about him getting killed this way.”

He cites John Bachar—a climbing legend who blazed new trails both free soloing and with ropes, and is an almost mythical figure in Yosemite climbing history. He died free soloing in 2009 at age 52 near Mammoth Lakes, on a route he often used to warm up for harder climbs.

But Honnold says that free soloing gives him something that other types of climbing lack. “The experience is more fulfilling because it demands a lot of you,” he explains. “That’s soloing in a nutshell. Physically, it’s nothing harder than doing the stuff with the rope on. Mentally, there’s so much more to it. Because it requires you to give all that extra, you do get that much more back from it. It is that much more satisfying.”

*******

Honnold may have nurtured his audaciousness to epic proportions, but the seed of it comes naturally. He was, his mom says, destined for the vertical. “It was a nightmare,” Wolownick recalls of his childhood. “He was different from other kids from the very beginning. He was a climber from the day he was born. If I didn’t know where the baby was, I’d look on the top of the refrigerator.”

That’s not a joke. Even before his first birthday, Honnold was fully mobile and would scale appliances, shelves, even the water heater—and he rarely slept, waking before 5 a.m. and refusing bedtime until after 10.

It got to the point that the exhausted parents would leave a bowl of cereal on the table for the early-rising baby. “We started doing that from eight months on,” she recalls. “This one day, I wake up at like 5:30 in the morning [and think], ‘Why didn’t he wake me?’ ” She found the snack bowl empty but there was no sign of her son. Finally, she looked in the backyard, “and there is my 10-month-old baby standing on the top of the slide in his little onesie pajamas holding his blue blankie.”

It wasn’t until he was 11, when Granite Arch Climbing Center opened in Rancho Cordova, that Honnold got serious about climbing. Soon, he was there every day for hours, scaling the walls while his father secured the rope for him. When no one could drive him, he rode his bike. “Anytime I bike the American River Bike Trail I’m like, ‘Oh, home sweet home,’ because I spent years commuting on the bike trail,” he says.

Despite his endless hours in a harness, he excelled at academics, graduating from Mira Loma High School’s International Baccalaureate program with a 4.7 grade point average. He was shy, but smart (he belonged to the high-IQ club Mensa until he let the membership lapse) and he speaks multiple languages (his mother raised him speaking French and he later picked up Spanish).

“He can converse on just about any subject you want to talk about,” says his friend, Robinson.

Honnold got into UC Berkeley, but he didn’t like college. He lived off campus, had few friends and rarely went to his engineering classes—preferring instead to climb in the nearby hills. When his father died and left behind insurance money for both kids, he decided to leave school.

Honnold is circumspect about his father’s death. But, “In some sense I think it was a little freeing,” says Stasia Honnold of how her brother was affected.

Liberated from school, Honnold headed to Scotland to compete in the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation’s World Youth Championship (where he came in a disappointing 39th), then came back to the states, bummed his mom’s old minivan, and started down a road he’s still on today being a “dirtbag” climber.

He began free soloing at Lover’s Leap off Highway 50, west of Tahoe near the town of Strawberry, on easy routes called Knapsack Crack (which goes 300 feet up) and Corrugation Corner (a steep climb for beginners), and in 2007 showed up at Yosemite with no fanfare and soloed two notoriously difficult routes—the Rostrum and Astroman—in a single day. That feat instantly put him on the world climbing map. The next spring, he soloed the Moonlight Buttress in Zion National Park on April Fool’s Day, a climb so difficult (he scaled 1,200 feet in 83 minutes) that many thought it was a prank when word got out. Next up was the iconic, 2,000-foot-tall Half Dome.

After those history-making accomplishments, Honnold became a media sensation. 60 Minutes did a story on him; National Geographic put him on the cover in an iconic photograph on Thank God Ledge, a 40-foot-long thin protrusion barely bigger than his feet 1,800 feet up the side of Half Dome.

His skill has earned him sponsorships from companies including The North Face and Clif Bar, which provide him the income he needs to be a full-time professional athlete, and then some. It has also put him in the company of the world’s top climbers—especially through The North Face, giving him opportunities like ascending El Sendero Luminoso. “The sponsors pay me a salary and they basically just expect me to be a good ambassador,” he says of why he has embraced the attention in recent years, despite being uncomfortable with the recognition at first. “They expect you to climb well, like make news in climbing.”

But he lives a simple, almost ascetic life, in part, he says, because he doesn’t want to be “a douche.” Not being a douche is an important concept to Honnold. But he does have his own van now—a white 2002 Econoline that Robinson has tricked out with solar panels, a stove, LED lights and more. It’s Honnold’s home now (he lives on the road, stopping in Sacramento a few weeks a year to visit), nearly all of his possessions tucked neatly in bins and drawers under the built-in bed.

Honnold and climbing partner David Allfrey celebrate breaking the speed record on El Capitan’s Tangerine Trip route. (Photo by Max Whittaker)

He also started his own foundation dedicated to environmental projects (and has pledged to fund it with $50,000 annually). Recently, he completed a 700-mile bike-and-climb tour of the Four Corners area where Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah come together on what is largely Native American land, with friend and fellow climber Cedar Wright (it was the second time they had done this—the first one was dubbed Sufferfest and covered California’s 18 largest peaks). That mission ended on Navajo territory in Arizona, where Honnold volunteered on a solar energy installation project he had helped to sponsor—installing panels on the homes of American Indians who were not on the power grid. There are about 18,000 people on these lands without access to electricity, he says. “Seeing somebody turn on a light for the first time,” he says. “It was cool.”

*******

Seven hours and 56 minutes after Allfrey started his timer, he and Honnold reach the summit of Eagle’s Way. They have smashed the time record with ease. Both are amped from the climb and say it went smoothly despite the slippery start.

Honnold has popped the performance shoes off his heels somewhere along the way. They are clinging to his toes, tied tight across the midsole so they don’t fall off. This is how he climbed part of the route, shoes half off—a detail so insignificant to him he says he probably won’t even remember in a year.

Still, he’s happy when the forgotten shoes are delivered to him part way down the 3,000-foot descent, and so relaxed that he and Allfrey are talking about if Honnold’s girlfriend, Stacey Pearson, will be able to escape jury duty to go on a sport climbing trip. Then it’s a fast hike down the East Ledges in the stifling afternoon heat to the valley floor and back to the van for dinner and sleep. This is, after all, only day three of seven.

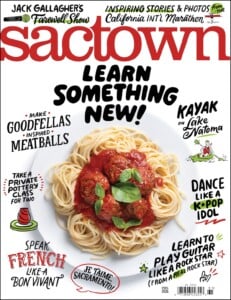

Honnold plans to free solo Taipei 101 (shown), which was, until 2010, the tallest building in the world.

By the end of the week, Honnold and Allfrey have completed their mission, breaking four speed records along the way. It’s another history-making feat. But within days, Honnold will be off to another adventure, and another. One involves climbing the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco for a commercial for insurance provider Stride Health, a free solo he pumps out in a matter of minutes while cameras track him up the fluted columns. Then he heads to California Street to climb a seven-story building, digging his fingers into the grout of the brick façade—just a little practice for Taipei 101. It’s a charmed life for a kid who started out on refrigerators, and it’s easy to understand why he’s not ready to quit.

“Hopefully, I’ll do more with my life than just climb forever,” he says as he organizes his van in his mom’s driveway in Carmichael in late May. He loaned the Econoline to a friend while he was abroad, and it’s been returned with hippie pillows, broken gear and a mock parking ticket from a Yosemite ranger citing the driver for “impersonating a rock star.”

Honnold stands near the stove hunched over, too large for the space, sorting through a stack of North Face shirts chosen by his girlfriend and sent to him by his sponsor. The ones deemed “so loud and so ugly” that he “cannot wear these ever,” are evicted and tossed into the garage, to be dropped off at a climbing gym as freebies.

He’s not sure where the summer will take him, much less the future. He has a lot of plans besides Taipei in the works. He recently signed his first book deal (with W.W. Norton & Company). He’s also been shooting scenes for an upcoming film he’s in called Valley Uprising, a documentary about the history of climbing in Yosemite premiering in September. There’s also the foundation, something that he can see taking more of his time, or maybe even a return to college someday to finish his education.

But, he says, putting the surviving shirts in a drawer under the bed, “for now, my main passion is just going climbing. That’s enough for me.”