Trigger Effect

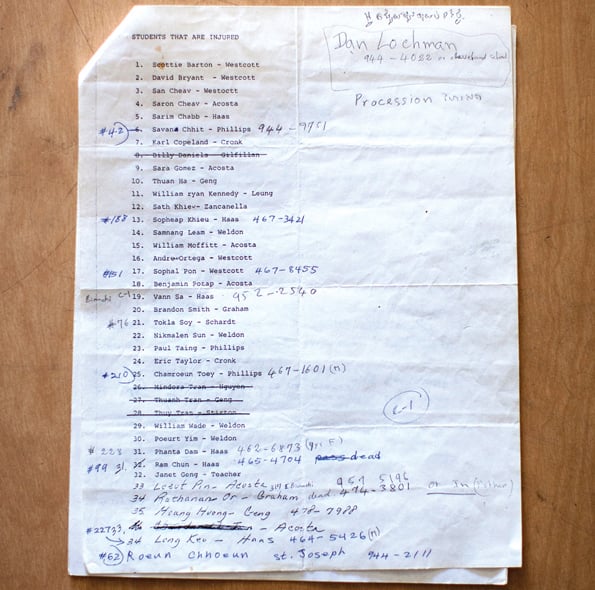

Sovanna Koeurt still has the list. She stores it at home in Stockton, where it remains filed alongside various notes, documents, news clippings and artifacts rooted in one day in 1989. She kept other lists from that day, too, but when she talks about everything that happened, she mentions this list—the first one. It is a single page, gently dog-eared on the upper left corner and creased into equal, yellowing eighths. She doesn’t recall who gave it to her. Maybe a police officer. Maybe a teacher. The source is no more and no less knowable today than it was on that January afternoon when Koeurt hurtled out her apartment door and into the cold abyss of panic less than a mile down Fulton Street. There are plenty of things she does know from that day. Visions she can’t shake, sounds she can’t unhear. She knows why she ended up with the list. She knows that her friends pulled her into action. She knows, as their neighbor and advocate, why its burden fell to her. She knows all but a few of the names. She knows their families. She knows their language. She knows how she came to unlock the list’s secrets—its horrors and reliefs—for them amid the tears and chaos and confusion. She knows the rush of numbness that accompanied receiving the list in the first place, and the wailing that still sometimes reverberates around her. The crowded grasping of hands and thunder of voices. The church walls closing in.

Sovanna Koeurt, photographed in the offices of the Asian Pacific Self-Development and Residential Association in Stockton, acted as a liaison between Cleveland Elementary School and the Cambodian community (four of the five students killed were Cambodian) in the aftermath of the shooting. (Photograph by Max Whittaker)

Koeurt knows she heard the other parents’ cries grow distinct—desperate men and women awaiting word about their children. The eminently familiar native tongues, curses in Cambodian. She’d spent many evenings working to teach some of them English, and now only she—not a cop, not a teacher, not anyone else—could answer them in the noonday havoc.

“Come on, read it!”

But she couldn’t. Not aloud. Not yet anyway. Not until she searched for her two sons among 32 typewritten names that flanked the left margin beneath a heading in capital letters: “STUDENTS THAT ARE INJURED.” Her sons weren’t on the list, but she didn’t know what that meant for more than an hour, when the lockdown ended and the boys ran from a classroom to finally be reunited with their mother.

She knows that the reporters interviewed her, and the panic faded to a pall. She needed to add more students to the list. Their names pooled in blue and black ink at the bottom of the column.

At the time, many were strangers to Koeurt, but she knew one of the boys: Rathanar Or, a 9-year-old who played basketball every day with her son Viseth. They were best friends until that morning, when a 24-year-old man named Patrick Purdy walked onto the school grounds with a semiautomatic rifle and fired 105 rounds at the children. Rathanar was shot and killed just before noon.

Koeurt still has the list and its indelible annotations—names and ages and hospitals and nightmares hand-printed around the page.

Procession.

Mother.

St. Joseph.

(7ysF)

Dead.

Cleveland School.

********

There is another list. It belongs to nobody and everybody. We reclaim it every few years from the anguished ether. New names once again join old names, strangers coming into focus, demanding reckoning. The list is shorter than the one Sovanna Koeurt keeps, yet it begins on that page, and it grows crueler across the decades. It winds through milestones and mythologies, tragedies we know by heart if less and less by memory.

Stockton. Iowa City. Lindhurst. Westside. Thurston. Columbine. Red Lake. Nickel Mines. Virginia Tech. Northern Illinois. Oikos. Sandy Hook.

Twenty-five years removed from the beginning, there is no end. There are 125 dead, 160 wounded and counting in the inexorable epidemic of mass shootings at schools in the United States. There is that epochal massacre on that Stockton playground a quarter-century ago, and there is the year since a gunman ended the lives of 20 first-graders and six school staffers in Connecticut. There are the families and survivors and communities adrift in the aftermath. There is the pattern of shock and grief that greets each killing, followed by pageants of indignation and irresolution that have plagued the issue of gun violence for a generation.

It’s true that shootings had transpired on American school campuses long before Purdy killed five students and wounded 29 more (plus a teacher) at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton on Jan. 17, 1989. The first recorded instance came when four Lenape warriors shot an instructor and scalped him and 12 of his pupils in 1764; nine of the children died. The University of Texas was the site of one of the 20th century’s most notorious mass shootings in 1966 when Charles Whitman killed 14 people and injured 32 others from his perch atop a campus tower. In 1988 alone, at least four schools nationwide were targeted by people with guns, resulting in a total of three students killed. Historically, school shootings and their victims make up a minuscule fraction of the nation’s firearm casualties. In terms of pure numbers, the shooting at Cleveland School barely cleared the FBI’s definition of a mass murder, in which a killer takes four victims’ lives, typically in one location without interruption.

Yet the event in Stockton had an unprecedented impact on the American psyche, which has struggled ever since to reconcile the image of fallen kids with the power of its gun culture. As the first mass school shooting since the advent of CNN, it stunned and galvanized viewers in breathless televised loops. Within months of Purdy’s rampage, lawmakers up the road in Sacramento had passed America’s first major gun-control legislation, including statewide bans on 75 types of firearms (including the Norinco AK-47 rifle, Purdy’s main weapon). The nation’s gun-rights proponents, led by representatives of the three million-member National Rifle Association, fought back with lobbying and recall efforts that it wields effectively to this day. And from Stockton to Newtown, Conn., and everywhere else these grim anniversaries await, the echoes of gunfire and rhetoric dissolve around the heartbreak, heroism and recovery of those who were there. Then, at another ravaged school, the cycle that started at Cleveland resumes.

“Whenever I read about the shooting in Connecticut, they don’t mention Cleveland at all,” says Koeurt, 59, who emerged as the leader of the sizable Cambodian community that settled in Stockton in the 1980s after escaping their homeland’s genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. More than two-thirds of Cleveland Elementary’s 975 students at the time of the shooting were Southeast Asian; four of the five fatally wounded children were Cambodian. (The fifth, 6-year-old Thuy Tran, was Vietnamese.) From the fraught sanctuary of Faith Lutheran Church, next door to the school, Koeurt communicated status updates to the other Cambodian parents desperate for news about their kids. Later, Koeurt identified the body of 6-year-old Sokhim An. “How many times do they not realize that this has happened?” she asks. “It’s like they’ve forgot about it completely.”

That sentiment singularly haunts the Cleveland legacy. Life in Stockton has gone on since the helicopters lifted bleeding children off the field, since the custodians patched the bullet holes in time for classes to resume the following day, since the massive counseling effort got underway for victims and witnesses. Twenty-five years later, however, it remains the flashpoint of an unthinkable phenomenon—the place where differences would be made and yet, somehow, nothing would change.

Nan Tran holds her granddaughter Thu, who touches a photograph of her sister Thuy three days after the 6-year-old was killed in the Stockton school shooting. (Photograph by Paul Sakuma/AP Photo)

“We had to do something about it and [try to] make sure it didn’t happen anywhere else,” says Gary Gillis, a retired Stockton fire chief who reported to Cleveland in 1989 as a paramedic. “We went up to Sacramento. Our voices were heard. We went in the right direction. We did what we could. So there’s great pride in Stocktonians that we were able to warn the rest of the country: It’s going to happen to you. Some Stocktonians thought, ‘Well, it’s only going to happen here,’ or whatever. But unfortunately it’s borne out that it’s happening more and more. Not just in the United States now; it’s happening all over the world. I think that Stocktonians are resigned to the fact that it’s going to continue to happen unless [others] listen to what we said in 1989. We were virtually one voice, one community saying, ‘You’ve got to do something about this, because we don’t want anyone else to suffer from this.’”

Even as the city and the country struggle with their implications, the events of Jan. 17, 1989 have imprinted Stockton with a tragic and oft-overlooked significance: In the modern era of school shootings, no place in America has more years of experience answering the only question arguably more crucial than “Why?”

“What next?”

********

How it sounded at first depended on where you were at approximately 11:45 a.m. Many of the kids on the playground or field thought they heard firecrackers. From her classroom, a fourth-grade teacher mistook it for a drum tap. A 911 caller who announced himself as a Vietnam War veteran declared it was fire from an AK-47 rifle. The dispatcher summoned her supervisor. “Listen to this,” she told him before replaying a tape recording of the call. They couldn’t hear the sound in question but were struck instead by the caller’s certitude. “You could tell from his voice that he was dead serious,” recalls Ken Uehling, who oversaw the Stockton fire and medical dispatch center on the morning of Jan. 17. “This was not a prank. He knew what he knew.”

Uehling called Engine 9, which the dispatch center had sent moments earlier to investigate a burning car on Stadium Drive, just behind Cleveland Elementary School. He relayed to the crew that a caller heard shots fired, advising them to proceed to the site with extreme caution. He called Stockton Police to alert the watch commander. By the time Uehling ended the call, the center was swamped with new reports confirming gunfire at Cleveland.

One mile southeast of the school, firefighter Kim Olson was off duty at St. Joseph’s Hospital. He typically flew as a paramedic on the emergency helicopter Medi-Flight 2, but on this particular morning he found himself irretrievably on edge, tense with nerves and some vague dread he couldn’t place. He went to the coffee room and caught up with another paramedic whose radio crackled to life with Uehling’s advisory: “Shots fired.”

The other paramedic was dispatched to the scene and left for the school. Envisioning the worst and worrying that helicopters might be ignored in the developing frenzy, Olson called flight dispatch, followed by a call to the dispatch center for Stockton Fire.“We’re gonna launch Medi-Flight 2,” he told the head dispatcher. “Go ahead and launch Medi-Flight 1.”

Seven-year-old Paul Taing was at recess with the rest of the primary schoolers. The slaps of a red rubber ball on the four square court ceded to piercing blasts. Brandon Smith heard the bangs as well on the field, where the 9-year-old was playing football. From the unseen, unknown distance, a voice yelled to them and his Cleveland School classmates. “Run! Somebody’s shooting!”

Wirephotos of the five Cleveland students killed during the 1989 massacre: (Clockwise from top left) 8-year-old Oeun Lim, 6-year-old Ram Chun, 6-year-old Sokhim An, 6-year-old Thuy Tran and 9-year-old Rathanar Or.

Taing ran. Smith ran. They all ran. First-graders, second-graders, third-graders, teachers, monitors, every kid in their sweaters and winter coats, new shoes delivered by Santa Claus, shrieking and pounding over asphalt and turf, through the din, over the din, toward the safety of the school. Hundreds of bodies racing, churning until bullets started finding them like sideways rain.

Rathanar Or ran. First-grader Robby Young sprinted behind him from the kickball court. Young thought he heard firecrackers, too, before Or seized and tensed up and fell to the playground roughly 20 yards in front of him. Dead. Young kept moving. He figured that if he could just make it to the wooden handball wall in the middle of the yard, he would be all right. Fifty yards. He could get there. He scanned the chaos. He hunted for his best friend, Scottie Barton, lost in the stampede. Young’s search had turned his body toward the rear of the school, the origin of the shooting. He didn’t see Scottie, and he didn’t see a shooter, but he felt his feet lifted from beneath him and over his head as he went tumbling to the blacktop.

Taing made it to a bench near his classroom when he was forced down by the bullet entering and exiting his right side—a clean, direct line from kidney to abdomen. He popped back up, flush with adrenaline and terror, hustling again to his classroom. His first thought was of his mother and family. “I started crying, but not because of the pain,” Taing says today. “Because I thought I would never see people again.”

Brandon Smith continued running, watching kids hiding behind sandbox barricades and jungle gyms. He’d seen one of his football buddies make it about 100 yards to a classroom. Smith figured he could also make it until a shot tripped him up. He didn’t fall, but rather fought off the warm numbness accruing in his left leg. He managed his way to a tree at the corner of the campus, looking back at a row of his small, bloody footsteps. Smith collapsed and pulled up his left pant leg. The bullet had blown through nerve and muscle just above his ankle but narrowly missed the bone. He contemplated his next move and his dead leg. He checked around him and spotted a classroom with the door open. “A teacher was pulling kids into the classroom,” Smith remembers, “and I tried to get up and walk to the door, and I couldn’t make it.”

Robby Young felt the heaviness in his feet and the jolt in his chest. A bullet had pierced his right foot, knocking him to the ground. An instant later, another round had shattered on the pavement in front of him, deploying its fragments into the left side of his chest. “I just remember how powerful it seemed,” Young recalls. “A lot of force.” Yet he’d made it to the handball wall, where splinters and debris exploded over his head as AK-47 rounds punched through the wood. Across the playground, he saw the open door of his classroom. Young stood up and made a sluggish dash through the last of the gunfire, blood pulsing from his foot and out of the side of his shoe. Finally he saw his friend Scottie Barton sitting on the blacktop, where a yard supervisor scooped Barton up and took off running.

Olson and a nurse, Gigi Nault, departed from St. Joseph’s Hospital with their pilot. Lifting off from the roof in Medi-Flight 2, Nault looked down at kids frolicking at a school across the street. Thirty seconds later their helicopter was forced into an orbit around Cleveland until the shooting finally ended. When it did, and Medi-Flight 2 flew back in over the school, Nault was struck by the contrast between playgrounds. She watched a ball bounce along, rolling and glancing off one of five still bodies lying on the blacktop, covered with a jacket.

“We’ve got five on the ground,” firefighter Olson said.

“No,” Nault said, disbelieving. “Those are just clothes. Those are just coats.”

At the dispatch center, Uehling and his dispatchers started receiving calls from news reporters to 911. “We’d just immediately hang up on them,” he says.

Gary Gillis, then a Stockton Fire captain, pulled up to the back of Cleveland School with his men on Engine 7. The firefighters from Engine 9 had already extinguished the car fire reported by dispatch. Their driver pointed to the gap in the fence. “They went in through that gate,” he told Gillis, gesturing toward his crew on the school grounds. “And they’re gathering up kids.”

A young Cleveland elementary student, who was wounded in the chest during the shooting, receives medical attention. (Photograph by Michael Chow/Getty Images)

“By then we’ve all figured out what’s going on here: That somebody randomly is shooting kids on the campus,” Gillis says today. His team retrieved their gear and followed their colleagues through the gate. They had drilled and prepared for mass-casualty incidents, but there was no protocol for responding to an active shooter at an elementary school. Was the shooter even neutralized? Were there multiple shooters? Gillis was confident that the city’s first responders would deliver on their training. He just couldn’t know at the time if they were about to become targets as well.

At 11:50 a.m.—five minutes after the shooting began—Gillis approached a police officer standing at the fringe of the playground. In front of the officer, Gillis saw a body crumpled on the ground. It was a male, wearing a bulletproof vest over a camouflage jacket, still breathing despite a severe gunshot wound to his head. “That’s the shooter,” the officer said.

********

Patrick Edward Purdy used to be one of them. He had started kindergarten at Cleveland Elementary School on Sept. 2, 1969—a little more than two months before his fifth birthday, and a little less than a year after his mother Kathleen married his stepfather, Albert E. Gulart, in Reno. Along with Purdy’s sister Cynthia and infant brother Albert Jr., the new family settled in Stockton. Patrick would eventually complete first through third grades at Cleveland, winding down his primary education there just as his mother wound down an abusive marriage to Gulart. The couple divorced in 1973, at which time Purdy’s mother moved herself and her three children up to Sacramento.

Shooting victim Rob Young, now a police officer, stands with one of the rifles in his gun collection at his home in Stockton. (Photograph by Max Whittaker)

An October 1989 report to the California attorney general about the Cleveland shooting describes one of Purdy’s early encounters with police, when officers in Sacramento responded to a neighbor’s report of three children left home alone. The kids spent the night in protective custody; his mother faced child neglect charges when the incident repeated itself two days later. (Charges were dropped after Kathleen Gulart attended counseling.) Purdy was in the process of repeating fifth grade at Joseph Bonnheim Elementary—about a mile south of Sacramento State University and closed this past June—when his mother moved the family again, this time to South Lake Tahoe. The attorney general’s report cites “intense conflict” between young Patrick and his mother at this time. She threw him out of the house in the summer of 1978. Purdy was 13. In later psychiatric evaluations, he would describe his mother as being “good at making you feel like an ass,” a “sick witch epileptic” and “the slave driver mother dearest.”

The rest of the report maps the dysfunction, alienation and sickness that plagued the remainder of Purdy’s short life and steered him to the Cleveland campus in January 1989. When he was 14, the transient teen was arrested in South Lake Tahoe for possession of stolen property and dangerous weapons; a few months later, while living with his father in Lodi, he underwent treatment at a Stockton drug and alcohol rehab clinic. In a mental health evaluation at the time, Purdy said he hated his mother and “could chop her head off.” His counselor wrote that Purdy seemed to be “seeking a father figure to restrain him” and concluded that “if his acting out is not contained now, he will develop into a highly deceptive sociopathic character and be practically untreatable.”

At least nine other arrests preceded Purdy’s 18th birthday. Nevertheless, in 1983, the California State Bureau of Collection and Investigative Services licensed 19-year-old Purdy as a security guard. He worked less than a month as a guard for one Los Angeles firm, which was sued because of Purdy’s alleged neglect of duty at a local supermarket.

Two and a half months later, Purdy made his first recorded gun purchase. Despite his felonious weapon run-ins as a juvenile, his troubled psychological history and a record of drug and alcohol abuse so prodigious that the federal government would eventually classify him as disabled, Patrick Purdy had never been convicted of a felony as an adult. And so it was that on April 28, 1984, Purdy walked out of a gun store in Los Angeles as the new owner of an Excam Targa .25-caliber pistol.

Purdy quit another security job and returned to Sacramento, where he worked 23 days for Vanguard Security before failing probation. In August of 1984, he completed a report for the Social Security Administration that listed 12 previous jobs lasting an average of one month or less.

He grappled with his sexual orientation, confiding his growing torment and isolation to doctors. “I never seem to fit in with everyone else,” Purdy wrote on his vocational report. “They are either laughing at me, calling me a gay boy, talking behind my back, or something. I guess I’m just not good enough.” In a subsequent disability report, he confessed: “I’m gay and in the recent past I had some bad drug problems.” In two separate psychological evaluations in October and November 1984, doctors characterized Purdy as a drug addict with “borderline intellectual functioning” and being “moderately confused.” He was diagnosed with substance-induced personality disorder and determined eligible to receive Social Security disability benefits.

On April 14, 1986, a drunken Purdy sought treatment at the Sacramento Mental Health Center for alcoholism and “occasional suicidal ideation.”

On July 3, 1986, he bought a Davis .22-caliber pistol in Modesto.

That autumn, returning to the Sacramento Mental Health Center, Purdy told counselors, “I’m not thinking the way I should be thinking.” Purdy broke into tears, saying his mother abused him and that he felt “lonely and unloved.” He said he identified with a postal employee who shot his co-workers and that he heard voices urging him “to do things.” A doctor prescribed Thorazine and asked Purdy to return a week later. When he came back on Oct. 7, Purdy appeared to have improved.

The next day, also in Sacramento, Purdy bought a Browning 9mm pistol.

The gunman Patrick Purdy. (Photograph by L.A. County Sheriff’s Dept./AP Photo)

This cycle continued for more than two years. In April 1987, Purdy was arrested by an El Dorado County sheriff’s deputy while drunkenly shooting one of his guns in the forest. Purdy was later charged with vandalism, resisting arrest and assault on a police officer after kicking out the back windows of the deputy’s car in a rage. At the county jail in South Lake Tahoe, he attempted to cut his wrist with his fingernails and hang himself with a noose made from his T-shirt. One evaluator wrote that Purdy was “a risk, albeit ambiguous, to harm himself. He does however appear to be a greater risk to others. That is, he would probably hurt someone else before he hurt himself.” Another evaluation at Placerville’s Psychiatric Health Facility classified Purdy as “extremely dangerous” but competent to stand trial in May. Of the five misdemeanor charges he faced, Purdy was convicted of one: Discharging a firearm. He was sentenced to 45 days in jail and given three years probation.

On Aug. 28, 1987, in Stockton, Purdy bought an Ingram MAC-10 9mm pistol.

On April 8, 1988, he showed up to a Social Security disability evaluation drunk and strung out on cocaine.

On Aug. 3, 1988, while living with his aunt in Oregon and bouncing between welding jobs in Portland, he bought an AK-47 rifle— a Norinco 56S model, and his fifth gun purchase in just over four years.

Stockton Police Captain J.T. Marnoch holds up the AK-47 assault rifle that Purdy used to kill five children and injure 29 others. (Photograph by Rich Pedroncelli/AP Photo.)

On Dec. 12, 1988, after working short-lived jobs in Tennessee and Connecticut, Purdy bought five boxes of ammunition and ordered two magazines—one for 30 rounds, and a 75-round drum—for his AK-47. He picked the magazines up three days later, buying an additional four to six boxes of rounds for the Norinco.

On Dec. 28, 1988, back in California, Purdy bought a Taurus 9mm pistol, agreeing to a 15-day waiting period.

By 1989, Purdy had an attack in mind. Patrons at a bar in Stockton later told investigators that they’d seen Purdy stalking around in camouflage clothes shortly after New Year’s Day, bragging about his high-capacity AK-47 rifle and complaining about government benefits received by the Vietnamese.

“You’re going to read about me in the papers,” he had said, exiting the bar.

A witness claimed to have seen Purdy parked in his car—a white Chevrolet station wagon—at the rear of Cleveland Elementary School on Jan. 5. A janitor across town at Sierra Middle School said Purdy approached him in a classroom on Jan. 10, where he asked the janitor for a dollar before pacing on a private road just off campus.

On Jan. 13, when his waiting period finally elapsed, Purdy picked up his Taurus 9mm.

That night, he met his half-brother Albert Gulart Jr. in Purdy’s room—number 104— at the El Rancho Motel. Gulart, whom state investigators interviewed in February 1989, said they cleaned Purdy’s weapons, loaded ammunition magazines and talked about killing people.

“Let’s do it,” Purdy said. “You’re not ready,” Gulart replied. “You’re right,” Purdy said. “Fuck it. They’re not worth it.”

Coronors carry out the body of Purdy, who shot himself after the rampage. (Photograph by Walter J. Zeboski/AP Photo)

And yet on the morning of Jan. 17, Purdy stood clutching the Taurus on the playground at Cleveland Elementary. He’d dropped the AK-47 after expending 105 rounds—75 from the drum magazine, 30 more from the other clip—over roughly two minutes. No one heard him say anything as he fired at the students from 200 feet away. He paused only to move around the back side of a portable classroom structure, resituating himself with a more direct line of fire at the playground and main building. Purdy’s orange earplugs deflected the screaming and the clamor around him. He probably didn’t hear the pipe bomb that he lit when it exploded in his station wagon, or Engine 9 as it roared around Stadium Drive to find the car fully immolated, black smoke lunging at the heavens. There is no telling if he heard the helicopters circling overhead, or his mother’s voice, or his remaining heartbeats or even the blast of the 9mm pistol as he pulled its trigger, firing into his right temple.

********

Assembly Bill 357 was kind of a do-over for Mike Roos. In 1988, the Assembly Speaker pro tempore tried to apply the same 15-day waiting period already in effect for handgun sales to purchases of semiautomatic firearms. That effort failed in the Legislature, but it began a conversation between Roos, police chiefs and other law enforcement officials statewide about how to craft a law that might better regulate the over-the-counter proliferation of military-style weapons in California. After some revision, Roos’s new bill sought to prohibit the sale and manufacture of specific guns—mostly rifles, including all AK models, the Colt AR-15, the UZI, and the Bushmaster assault rifle—as well as ban ammunition magazines with a capacity larger than 10 rounds. Over in the Senate, meanwhile, president pro tempore David Roberti introduced a bill almost identical to Roos’s. The idea, Roos says, was to give the proposed laws two chances to survive the opposition of gun industry lobbyists who’d thwarted similar efforts in the past.

Roberti and Roos didn’t need two chances.

“The bill was actually in print, moving or scheduled for hearing,” Roos recalls. “Then, of course, this Stockton schoolyard tragedy only amplified the necessity and frankly accelerated the urgency.”

By April, the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989 landed on the governor’s desk, where George Deukmejian’s signature made it the first extensive gun-control legislation passed in America. Shockwaves from the Stockton massacre headed east, where legislatures in Colorado, Texas, Florida and over 10 other states considered bills of their own to curb access to semiautomatic weapons and enhance background checks and other screenings for would-be gun buyers. On the federal level, even as newly inaugurated President George H.W. Bush publicly balked at any restrictions on the sale of semiautomatic rifles after Stockton, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms instituted an importation ban on those like the Chinese-made Norinco 56S rifle that Purdy bought in Sandy, Oregon—the AK-47 variety also name checked in the Roberti-Roos Act.

“It was the Cleveland School, probably because it was just all little kids, that highlighted it as nothing else had ever done,” Roberti says. “With their martyrdom, we were able to pass the legislation and give some footing to the pro-gun control people. In California, we never had that kind of footing vis-à-vis the gun lobby.”

The National Rifle Association temporarily moved its spokeswoman from Washington, D.C., to Sacramento and fought the anti-gun zeal with a marketing campaign evoking Purdy’s criminal history. “America had a place for Patrick Purdy,” said an NRA newspaper ad featuring a jail cell door. “But seven times the system set him free.” Certainly, the attorney general’s 1989 report on Purdy revealed numerous red flags, failings and oversights that foreshadowed his attack. Furthermore, with Purdy never having been convicted of a felony and with his mental-health history off-limits to the state, nothing in his public record would have prevented him from obtaining legal firearms in California even after Roberti-Roos became law.

On paper, the landmark law showed little positive effect in the years immediately following its passage. In keeping with the national trend, gun deaths in the state actually increased, ballooning to nearly 18 Californians per 100,000 killed by guns.

Michael Jackson visits Cleveland elementary School a few weeks after the shooting.

“We realized that we were in an epidemic,” says Garen Wintemute, a doctor at UC Davis Medical Center who specializes in the study and prevention of firearm violence as a public health risk. While mass shootings remained relatively anomalous nationwide, rates of gun homicides, suicides, accidents and other fatalities began to achieve levels that epidemiologists like Wintemute hadn’t seen outside statistics dating to the 1930s. “Those rates peaked in 1994 or so,” he adds, “at a time when it looked for all the world that firearms were going to overtake motor vehicles and come out as [the leading] cause of death from injury.”

In 1994, led by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the United States Congress passed a national assault weapons ban rooted in California’s seminal 1989 law—with one key distinction: The “sunset provision” that would automatically lift the ban after a decade if not extended by Congress. Roos backed the clause then, and he says he’d make the same deal today. “You want to get that on the books,” he explains. “Pray for a permanency, pray for the hope of a new membership that is more aligned to your viewpoint. She made the right decision, and it was historic.”

That same April in the San Fernando Valley, David Roberti faced a special election. The 28-year Senate veteran was in the middle of a race for state treasurer when a recall petition backed by the NRA successfully made the rounds of his district. According to a report in the Los Angeles Times, Roberti spent $800,000—nearly half of his campaign funds—to defeat the recall effort. Roberti’s opponent in the Democratic primary, Phil Angelides, beat him in June by 11 percentage points.

When asked about his loss, Roberti hesitates. “Nothing’s going to come without a price,” he replies, his voice tense and stung with frustration. “So to that extent, yeah, it still sticks with me. But on the other hand, you run for office, and you want to accomplish something. After all is said and done, you’re not running to make money. You’re not running to be the most famous person in the world. You want to say, frankly, after it’s over, ‘Hey, we got something done.’ And we got something done. Can’t be taken away from me.”

The exile of a Sacramento power player like Roberti signified a new milestone in the post-Cleveland gun culture: The NRA was on the offensive.

Under the guidance of its new executive vice president, Wayne LaPierre, the association’s leadership swiftly answered critics within its own ranks who saw its response to the raft of new gun laws as rudderless and soft. When a 1993 article in the New England Journal of Medicine linked keeping a gun in the home to an increased risk of homicide, the NRA lobbied to shutter the wing of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that funded the article’s research. Although that wing—the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control—stayed open, federal budget language three years later forbid any funds made available for the CDC’s efforts in injury prevention to “be used to advocate or promote gun control.” Researchers focusing on gun violence in streets, cities and schools nationwide couldn’t be sure which of their studies might next jeopardize their colleagues or the CDC itself.

“If you have an interest in preventing policy change and selling your product, and the research is your problem, stop the research,” Wintemute says. “It made perfect sense from their point of view. All of us at the time understood what was being done and why.”

On the heels of the Stockton massacre, a Time magazine cover story called attention to the rise of gun-related deaths in America.

Yet policy skirmishes in Washington, where the federal assault weapons ban had just taken effect for at least the next decade, could only go so far toward restoring the NRA’s member morale. In an infamous 1995 fundraising letter to the rank and file, LaPierre attacked the Clinton administration: “It doesn’t matter to them that the semi-auto ban gives jack-booted government thugs more power to take away our constitutional rights, break in our doors, seize our guns, destroy our property, and even injure or kill us.” (The first President Bush, a longtime NRA member, left the group in protest.)

LaPierre apologized, but the inveterate Washington firebrand had set the tone for the conversation to come: The gun-control wave rippling out from Cleveland Elementary represented a different kind of epidemic for Second Amendment disciples. From recalling legislators to challenging researchers to inveighing against new laws, the NRA recognized and repurposed their adversaries’ potent life-or-death message. It wasn’t strictly for show when Hollywood icon and five-term NRA president Charlton Heston lifted a rifle over his head at the 2000 NRA convention, invoking the mantra that his foes could take the gun “from my cold, dead hands.” It was a summation of everything guns meant to anyone who’d seen or felt their astonishing power. For gun supporters and foes alike, survival itself was at stake.

********

It’s a warm September evening in Stockton, almost the end of summer, and the sun slowly sets behind the curving steeple of the Central United Methodist Church. Just before 7 p.m., Judy Weldon stands at the whiteboard in Room 6, writing in her impeccable teacher’s print: “Agenda. Sept. 17, 2013. Welcome. Introductions. Housekeeping. History. Letter to Governor.”

The letters are already written for anyone attending tonight’s inaugural public meeting of Cleveland School Remembers, a group of six former teachers who watched, listened and reacted as Purdy opened fire on their students. Running, they grasped and sheltered wounded kids. They strained for order and solace in the lockdown after Purdy’s suicide. They navigated around and eventually identified the lifeless bodies of children who’d fidgeted into the thrall of a lesson or a story just a few hours earlier. They stood and struggled to comprehend or even know anything. Brought out to identify one of the dead children, neither Weldon nor second-grade teacher Julie Schardt could be absolutely certain that the girl with the head wound was their student Oeun Lim. “It was such a surreal experience,” Schardt says. “I remember it was cold, and I remember her red shoes.”

Much else has faded about the Cleveland shooting since it seized the American imagination—since Time grimly proclaimed “ARMED AMERICA” in a cover story three weeks after the massacre and, later in 1989, Esquire painstakingly deconstructed the last days of Patrick Purdy. No less a pop cultural eminence than Michael Jackson invited himself to Stockton on Feb. 7 of that year, where his attempts to cheer up the Cleveland community only meant more emergency vehicles, more police, more helicopters and more campus bedlam that just recalled the panic that Jackson had sought to assuage in the first place. The sights and sounds and mediated tragedy of it all receded as life went on in Stockton. Only in the year since Sandy Hook has memory emerged for these teachers as the mixed blessing of the Cleveland massacre, where a long-simmering synthesis of trauma and fury over slaughtered grade-schoolers has been channeled into action after nearly 25 years.

The group officially came together in February as a response to the shooting in Newtown, but not until September would they finally meet publicly at the church. “Help Us Reduce Senseless Gun Violence,” reads the front of Cleveland School Remembers brochures stacked up on the room’s back counter, wedged between fliers outlining California’s pending firearms legislation. Free booklets entitled “A Citizen’s Guide to Lobbying” instruct readers how to lobby for bills in person and testify before committees. Letter campaigns are encouraged, which is in part how the teachers came to have their pre-drafted letters on the counter, a sheaf of photocopies addressed to Gov. Brown. “Support: LIFE Act Firearm Legislation,” it urges, citing four specific Senate bills awaiting attention from the governor. The letter attributes a 52 percent overall drop in California’s firearm mortality rate since 1990 to the gun laws enacted after the Cleveland shooting. “Nonetheless,” the correspondence continues, “almost 6,000 Californians are injured or killed by guns every single year, a number still unacceptably high. The measures contained in the LIFE Act are critical to closing loopholes and protecting our communities from gun violence.”

The audience is made up of 17 attendees including the teachers, who had hoped for a little bigger showing for their first gathering. But there’s a representative from San Joaquin Grassroots Action here to offer advocacy tips, and a delegate from the local Cambodian community association has dropped by with an offer to translate the Gov. Brown letter for his constituency. Another of the teachers, Adrienne Egeland, proposes collecting a list of gun-violence data and talking points to better engage with gun proponents. Weldon takes the floor, acknowledging mental illness, gangs, bullying and other frequent factors in gun violence before getting to their common denominator.

“We have chosen gun violence because we feel we can make a difference soon with the gun violence issue,” Weldon says, raising the group’s brochure over her head. She taps the air, harder and more assertively with every few words. “And that’s why we are working. We have seen the carnage that gun violence brings about. So our mission is not mental illness right at this moment. Our mission is: Let’s do something to keep the guns—the tools—away from people who shouldn’t have them. It’s the gun.”

The day after the church session, Cleveland School Remembers reconvenes privately at a member’s house. They discuss their recent progress—the mailing list sign-ups from the night before, the development of a short documentary about the group, a letter in support of a legal brief filed in Connecticut against the National Rifle Association, which is fighting new gun laws in the state after the shooting in Newtown. They characterize this as the work they couldn’t do in 1989, when they were responding to a spectrum of challenges just to get their kids and themselves through the school year. “You’d start a lesson, and then it would all fall apart,” says Egeland, who was a first-year kindergarten teacher at Cleveland in 1989. “I’d make my lesson plans: ‘OK, tomorrow, we’re going to do this and this, and this and this.’ I start this, and then we’d get a certain ways into it, and we’d have to stop for crying or anxiety. Or something would happen from the outside that would come in.”

“There was a lot of that,” Weldon says.

“Some visitor or some counselor,” Egeland says.

“Some announcement,” adds Sue Rothman, another former kindergarten teacher at Cleveland.

“Or a reminder,” Schardt says. “So we read a lot of books,” Egeland says. “A lot of books,” Weldon says. “And then eventually,” Rothman says,“they told us we didn’t have to follow the curriculum. But in many ways that was harder.”

“We didn’t have to give the standardized test that year,” Egeland explains. “We had to push for that.”

Khorn Ing holds a portrait of her 6-year-old daughter Sokhim, who was fatally wounded at Cleveland. (Photograph by Max Whittaker)

They had to push for much more as well, requesting necessities as basic as walkie-talkies for yard duty and an exterior paint job to mask the bullet holes around the building. (The custodial crew had already spent the night after the shooting patching holes, replacing windows, shampooing carpets stained with blood and even repairing a tetherball pole cleaved by a bullet.) The teachers submitted a three-page “Needs List” to the Stockton Unified School District three weeks after the attack. When their requests went unanswered, they paid an unscheduled visit to the superintendent’s office. They soon became known around the district as “those Cleveland teachers,” but they got their meeting. “We eventually figured out that we needed to advocate for us because we were victims, too,” says Rothman. “They were not seeing us as victims.”

Listening to the teachers today, a bracing nostalgia sinks in. The work of Cleveland School Remembers is not simply activism that they couldn’t accomplish 25 years ago. This is work that they could never have imagined they would need to accomplish. A gun slaughter like this had never struck an American elementary school; the immediate shock and recovery obscured the long view of how and when such a shooting might happen again. Even as the horror recurred at campuses from California to Colorado to Virginia to Pennsylvania to Connecticut, many of those who’d witnessed it the first time hadn’t even developed a language or ability to process their own tragedy until decades later. Some of the teachers sought to avoid triggering flashbacks among colleagues who raced to shelter wounded kids or, like Weldon and Schardt, were conscripted to confront the ravages of the dead. “We didn’t know what everybody was feeling at the time,” Rothman says, “so we’d talk about other things and do other things.”

“But also,” Schardt says, “when Sandy Hook happened, it brought it all back to us, I think. It was like, we saw these pictures of these little kids. When they put the pictures of the kids on the TV, I just sat there sobbing—looking at those pictures and remembering those pictures of our kids and the same ages that they were, and thinking about their parents and their teachers.”

“I thought, ‘Again?’ ” adds Barbara Sarkany-Gore, who taught kindergarten at Cleveland Elementary before retiring in 1998. “Of course, I’ve always had this feeling, waking up the next day after Cleveland, and thinking, ‘Something’s wrong.’ And then that feeling of disbelief: ‘Did it really happen? How could it have?’ That feeling of disbelief while it was happening.”

“Right,” Weldon replies. “That it’s really happening, because it’s so weird. In a school. But now, it’s such an everyday occurrence. It’s not weird anymore. People just duck—duck and cover.”

Twelve recorded incidents in almost 25 years do not make mass shootings on school campuses an “everyday occurrence.” Yet smaller shootings and gun incidents involving schools arise much more frequently, often much farther below the national radar. In January 2013, while the country still reeled from the Sandy Hook massacre, four people died and 10 more were injured in seven different campus incidents across America. In October, less than one week after a 17-year-old fatally shot himself at a high school in Austin, Texas, a 12-year-old killed a teacher, shot two students and committed suicide in Sparks, Nev.

The Children’s Defense Fund estimates that, in America, 50 children and teens are killed or injured by firearms each day. In a lesson on telling time during her final year teaching at Cleveland, Weldon asked her students what they could do in five seconds. A 7-year-old boy stood up and shouted, “You can pop a clip in less than five seconds!” Recounting the story, Weldon mimics the boy’s hand motions: a swift, strong slap of the left hand to the bottom of a right fist clutching an imaginary handgun. “This is how they come to school,” she says. “They come with this knowledge—they come every single day, in your classroom.”

And so they come to other classrooms, and so the ghosts and fearful imagination persist—a fog of heartbreak pulsing with fervor and sadness and a sharp, subsonic dread. “When this happens, as far as a school, it’s not your child who’s been killed,” Schardt says. “But it’s one of the children you are responsible for. You are the main nourisher. You give them sustenance. Especially in primary—you are a parent. In loco parentis. You’re a counselor. You feed them. You’re a nurse. All of those things.”

With this in mind, the Cleveland teachers worry quite a bit about the Sandy Hook teachers, two of whose ranks (plus the school’s principal, psychologist and two teacher’s aides) died with their 20 first-graders one year ago. Not long after the shooting in Stockton, the teachers there received a letter of support from teachers in Winnetka, Ill., where, in 1988, a woman with three handguns killed a student and wounded six others at their school. After some deliberation with the district, the Stockton teachers welcomed the Winnetka teachers for a counseling meeting. “We looked forward to them being here, I remember,” says Egeland. “I thought it was really helpful.”

Cleveland School Remembers took an identical tack in April, extending its own offer of counsel to teachers in Newtown. A liaison for the Sandy Hook teachers replied with her thanks, assuring her counterparts in Stockton that their proposal would be reviewed in May. That was the last the Cleveland teachers heard from Connecticut.

“We said, ‘We’re here if you need us, and nobody else needs to know about it,’ ” Schardt explains. “I think we felt the need to talk to somebody. We thought, ‘Who else could understand this experience, at least from a teacher’s perspective?’ ”

But despite the unfathomable casualties, the suffocating media crushes, the instant notoriety and the long, barbed emotional tails that the schools’ massacres have in common, there are two notable differences informing the perspectives of teachers at Cleveland: Unlike Sandy Hook, many of them were eyewitnesses to the gunman’s rampage, and virtually all of them returned to campus as classes resumed—the very next day. “That school is being torn down,” Rothman says of Sandy Hook. “None of that happened to us.”

Meanwhile, according to a 2009 report in the Stockton Record, just 227 of Cleveland’s 975 enrolled students came back on Jan. 18. Egeland’s only kindergartner that day was a little girl whose mother couldn’t figure out why her daughter was the lone child on the school bus.

“She had been absent the day before,” Egeland says, “and her mother hadn’t heard the news.”

********

Khorn Ing still has the school portrait of her daughter, Sokhim An, that ran in The Record and other newspapers worldwide in the days following the shooting. She sets it on the coffee table in her house on the east side of Stockton, where she sits in a tidy, spacious living room with the window shutters closed. She hasn’t kept much else from that day or the period around it. She discarded most of the girl’s clothes and toys and other effects in the early 1990s. There is a small box somewhere in the house, inside of which Ing vaguely recalls storing some of Sokhim’s work from Cleveland School. But the box, like every keepsake before it, just reminded Ing how much she missed her daughter.

“When I keep, I think a lot,” she says in the clipped English that is her second language. “I cannot do anything, you know?” The box’s whereabouts are as unknown in 2013 as those of the condolence letter she says she received from President Bush in 1989. “I maybe throw away,” she says. “I don’t want to keep. They don’t help me with nothing.”

Ing presents the wallet-sized portrait along with a 3-by-5-inch snapshot of Sokhim’s dead body. She offers them matter-of-factly. They are less mementos to Ing than proof to her visitors of who was lost. In the latter photo, Sokhim’s black hair darts over her forehead, and a crimson bloodstain blossoms from the puncture in her sky-blue sweater. It’s the same sweater that Ing spotted on the playground in the raw moments after her husband told her there had been shots fired at Cleveland Elementary. She fled her residence at the Park Village Apartments, a heavily Cambodian enclave less than a mile east of the school.

“I run!” Ing recalls today. “I run too fast, you know? I leave Park Village, and I run from Park Village to Fulton Street, and just around, and then I saw it. And I say, ‘Oh my God!’ ”

Ing fainted upon seeing her daughter. When she awoke hours later at San Joaquin General Hospital, her friend Sovanna Koeurt was at Ing’s bedside.

“Don’t cry,” said Koeurt, trying to comfort her. “Your daughter…”

Ing claps her hands, bringing herself back to the speechless present. She shakes her head, silenced by tears.

![Paul Taing, then 7, was at recess when the shooting began and was hit by a bullet in the torso. “I started crying, but not because of the pain,” Taing remembers. “Because I thought I would never see [my family] again.” (Photograph by Max Whittaker)](/wp-content/uploads/data-import/f474f09a/StocktonShooting28202.jpg)

Paul Taing, then 7, was at recess when the shooting began and was hit by a bullet in the torso. “I started crying, but not because of the pain,” Taing remembers. “Because I thought I would never see [my family] again.” (Photograph by Max Whittaker)

“They say he’s crazy,” Koeurt explains from her office at the Asian Pacific Self-Development and Residential Association, a nonprofit organization she helped found in 1989 and for which she serves today as executive director. “We don’t believe he’s crazy. Maybe they have a lot of groups. We don’t know. We don’t come from a place where one person can kill a lot of people. A group kills a lot of people.”

The unprecedented massacre mobilized an equally unique outpouring of support for the immigrants in Stockton. Prior to Jan. 17, 1989, they were largely invisible beyond the walls of Park Village and outside the campuses of Cleveland Elementary and a handful of other local schools. The week of the shooting, though, as parents deliberated about sending their children back to school, Koeurt requested and received a dedicated fleet of buses to drive kids from Park Village to Cleveland. The school’s principal, Pat Busher, arranged for a Buddhist monk to visit the playground for a traditional blessing believed to ward away evil. City officials raced to learn customs and language that could stave off a mental health crisis among a population already ravaged by years of trauma and grief.

The challenge was huge: On the one hand, Stockton saw a need to combat the Southeast Asian community’s stigma of mental illness before they could adequately treat their symptoms. On the other, past research had shown the language barrier getting in the way of accurately diagnosing the immigrants who did seek help—flashbacks, hallucinations and other signs of post-traumatic stress disorder were sometimes mistaken as schizophrenia. Quickly they learned that the horror of the shooting had collided with the legacy of war and violence in Cambodia, crafting a sort of psychological superstorm.

Of course, many of the wounded were at an age when death made literally no sense. Seven-year-old Paul Taing, for example, got over his existential panic as soon as paramedics started cutting off his clothes; he was almost more upset about the destruction of his favorite striped sweater and blue pants than he was about being shot. It wasn’t until he was an adult that he acquired an appreciation for the regular Cleveland counseling sessions that he loved so much for getting him out of class.

Today, at 31, on the infrequent occasion that a stranger learns about his past and asks about his wounds, he unabashedly lifts his shirt to expose the muddy 12-inch line that has grown where doctors once cleaned out the trail of bullet residue that ran through him. He doesn’t register the scar in the mirror most days, and he doesn’t register mass shootings in the news as phenomena that have happened to him. “I mean, I think it’s very sad,” Taing says one morning at his home in Los Gatos, where news footage from that day’s mass shooting at the Washington, D.C., Navy Yard plays on a muted TV across the room. “But in terms of do I have flashbacks? No, I don’t. I just feel really bad for the victims and their families.”

Touch Lim sympathizes, too. He sees the shootings on TV but doesn’t catch where they take place, or learn how many died or were injured, or ask who is responsible. He doesn’t hear the debate that ensues—the gun-control pleas, the Second Amendment homilies. He just senses a wavering in the darkness that has shrouded most of his life, tragedy that climaxed with the murder of his daughter Oeun Lim. She was the fourth of his eight children to perish; three had starved to death in Cambodia, casualties of the Khmer Rouge. Oeun never made it to Sovanna Koeurt’s list of injured students; shot in the head just three steps from a school entrance, she died instantly.

Today, Koeurt interprets for Lim when people come around to ask about his loss. He says he was mad the first few times reporters and other interrogators visited, usually on the cusp of one milestone anniversary or another. Eventually, though, as he heard of new school shootings—new slain children, new grieving families—Lim felt a gradual release.

“Everybody is in the same boat,” he says. “I want to tell the other families that they shouldn’t mourn so much and be so sad, because it’s not only you or your family that lost your child. There are a lot of people you can see on TV—that other people killed their kids. We mourn for the kids, but they also mourn for the kids. I know that you have sorrow and loss, but if anything, we have the same feelings.”

For Ing and Lim, there is solace in moving on. There is no choice. For other Cleveland families, there is no solace. The killing of 6-year-old Ram Chun devastated her father Keut Chun, another Khmer Rouge survivor for whom the death of his oldest daughter proved too ruinous to bear. Koeurt mentions Chun’s inexorable slide into alcoholism. A 1990 Sacramento Bee report on the first anniversary of the shooting chronicles his suicidal thoughts and chronic depression; a 2009 Record report cites his death in 1998 from kidney and liver disease.

The family’s tragedy later found a staggering reversal at the very place Ram Chun died: Her older brother Rann now teaches second grade at Cleveland Elementary School.

Judy Weldon (top) and Julie Schardt (center), who were both teachers at Cleveland at the time of the shooting, attend a candlelight vigil at the State Capitol on Oct. 10, 2013 to urge Gov. Brown to sign the LIFE (Lifesaving Intelligent Firearms enforcement) Act. (Photograph by Max Whittaker)

Through a school district spokeswoman, Rann Chun declined to be interviewed for this article. His former Cleveland teacher Judy Weldon recalls a conversation they had as peers four years ago, when he said that he blamed himself for his sister’s death. He was supposed to be her protector, Rann told her—he was supposed to be her big brother.

“What he should have done was talked to me about it [earlier],” Weldon says, “because he didn’t remember being in lockdown. I said to him, ‘We can’t go outside the door. The door is locked, because they don’t know if some other bad people are out there.’ He did not remember that part, and the whole time, he blamed himself. He actually shared this in the teacher’s room one day after school. It was in passing almost. And the two of us are standing there in tears, and he’s not believing that. He should have been able to go down and help her. I said, ‘Rann, you are the person…’ ”

Weldon pauses.

“ ‘You are the person in my class that kept asking me … You asked me over and over again to let you go and find her. And I couldn’t. I couldn’t do it because I couldn’t open the door. You were [being] responsible. You were the big brother.’ ”

Tears catch Weldon’s breath.

“So even this many years later,” she finally says, “we’re just finding out some of these things. He carried this all of these years—not knowing, thinking that he was to blame when he wasn’t.”

********

It’s dusk at the State Capitol on Oct. 10, 2013, where candles and voices tremble on the west steps. Inside the Capitol, a stack of new firearms bills await Gov. Jerry Brown’s signature. Outside, gun-control advocates hold a vigil. The organizers intend to read the names of those Californians killed by guns since the Newtown massacre. That tally stood at 1,128 names when the event was conceived in early October; as the congregants gather a little more than a week later, the number has risen to 1,143.

Cleveland School Remembers is here. Julie Schardt talks on-camera with local television news reporters. Judy Weldon introduces herself before the reading of the names. She reminds the small crowd of the shots fired in Stockton on Jan. 17, 1989. “We know what bullets do to human bodies,” Weldon says. “We’ve used our hands as tourniquets to stop the flow of blood. We’ve identified dead children as they lay on the cold pavement of the playground. Tonight, we are here to support Governor Brown as he makes difficult choices.”

One hundred feet away, a lone protestor quietly faces the luminaria. His left hand raises a black flag emblazoned “DON’T TREAD ON ME.” His right hand cups a placard warning against government tyranny. He identifies himself as “Cougar”—30 years old, ex-military, a responsible gun owner. He hasn’t heard about the Cleveland School shooting or the laws that it sparked, but since witnessing the flood of proposed gun restrictions in California after Sandy Hook, he estimates he has been to at least 40 gun-related assemblies in and around Sacramento. “Our legislators have been using out-of-state incidents like Colorado and Connecticut as a way to push California legislation,” he says. “And that makes no sense at all. They constantly bring up Newtown, when Newtown laws actually worked. The kid went and tried to get a gun legally, [declined] a background check, wasn’t able to get one. So what’s he do? He kills his mom, steals her guns, and uses those guns. That’s not a law-abiding citizen at all. I’m law-abiding.”

The next day, Brown signed 11 of the bills into law, adding to the list of regulations that give California the nation’s most far-reaching gun policies. The new laws include a ban on lead ammunition and a mandate giving psychotherapists one day to notify police of patients who make violent threats toward “a reasonably identifiable victim or victims.” (Existing law already prohibited such patients from purchasing firearms within six months after a reported threat—if or when the threat is reported at all.) But Brown vetoed seven others, most notably SB 374—Senate president pro tempore Darrell Steinberg’s controversial legislation that would ban semiautomatic rifles with detachable magazines like the kinds used in mass shootings from Stockton to Newtown. In his veto message to the Senate, Brown cited the negative implications for hunters, firearms trainers, collectors and other gun enthusiasts. “I don’t believe that this bill’s blanket ban on semiautomatic rifles would reduce criminal activity or enhance public safety enough to warrant this infringement on gun owners’ rights,” wrote the governor, a gun owner himself.

The vetoes further reflect the entrenchments of America’s protracted gun-rights battle—a schism that runs deeper and deeper through those who were present at Cleveland School in 1989. Some, like the teachers and Sovanna Koeurt, don’t understand the purpose of semiautomatic weapons beyond killing. “They say it’s because of the game—hunting game,” Koeurt protests. “But how can you kill the deer with a rifle that’s 30 at a time? You’re not going to have meat to eat!”

On the other side, shooting victim Robby Young is now Officer Rob Young, a policeman in the Bay Area who has actively lobbied against new gun laws. He traveled to Washington, D.C., last February to speak in support of a bill that would repeal “gun-free zones” around American schools; a few months later, Young visited the State Capitol to testify against SB 374. He acknowledges the perceived irony of a shooting victim advocating against gun control. He also argues that for those threatened by an active shooter, every second counts. “Why not have somebody on campus that’s armed [and] can hopefully neutralize this threat and stop this threat before we get there?” asks Young, the father of a 6-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son. “By all means, if the cops get there, let us handle the situation. But why not have some security personnel, or administrator, or a teacher that’s able to carry a gun? We trust these people with our kids’ lives anyway.”

Brandon Smith, now 34, is a paramedic for a private ambulance company in Stockton. He credits his time spent in the hospital as a Cleveland victim with igniting an interest in doctors and nurses. By the time he was 12, he’d resolved to become a medic. He speaks to few people about being shot 25 years ago or about the arsenal he has acquired as an adult. “In fact,” he says, “I own the very gun I was shot with—an AK-47.”

Smith explains how the rifle complies with all state and federal laws—domestically manufactured, 10-round detachable magazine with a modified manual release—and that he doesn’t see anything macabre or strange about buying it. It’s simply the gun he likes to fire off at the shooting range. “It’s not like only crazy people are going to like that gun, or people who want to kill others are going to be attracted to that gun,” he says. “It’s just a firearm.” Others still, like Stockton first responders Gary Gillis and Gigi Olson—nèe Nault, who married her Medi-Flight 2 partner Kim Olson in 1989— emphasize preventing the abuse that leads to mental illness. “I’m very pro-gun,” Olson says. “I just could sit here and hate [Patrick Purdy] for what he did, but there’s an ugliness that was in his life.” Gillis himself admits exasperation with the fierce tenor of the gun debate, as well as sadness at the resignation that always follows the hype around every school shooting since Cleveland. “These people feel secure dropping their kids off at school,” he says. “What’s it going to take for them to know tomorrow it’s going to be your school? Or someone you know?”

Those close degrees of separation are what Garen Wintemute, the Sacramento-based doctor and researcher, believes will end the ideological stalemate over guns in America. “Whenever we have a public health problem, the numbers don’t tell the story,” Wintemute says. “Individual people tell the story. That’s just how we’re wired as a species.” He notes that it took years of awareness campaigns and a concerted effort by the medical community to legitimately confront the epidemic of HIV and AIDS. For now, Wintemute is one of a handful of physicians in the United States who focuses specifically on preventing gun violence that kills around 32,000 Americans and injures at least 60,000 more annually. “That’s just nuts,” he says.

Little, if any, commitment is foreseen coming out of Washington. Despite the ban’s support from then-President George W. Bush—whose father the National Rifle Association so memorably alienated in 1995—Congress let its landmark assault weapons law lapse from the books in 2004. Democratic senators up for reelection in right-leaning states like Montana, North Dakota, Alaska and Arkansas all opposed new federal firearms restrictions and enhanced background checks arising from the Sandy Hook massacre.

On the state level, gun advocates have revived the recall strategy that derailed gun-law trailblazer David Roberti’s political career 20 years ago. In Colorado, where a mass shooting in Aurora killed 12 people and wounded 58 others in 2012, an NRA-backed recall campaign ousted a pair of Democratic senators who’d voted this year for the state’s new gun restrictions. The organizers of that campaign have since turned to California, where they’ve targeted no fewer than five Democratic lawmakers who supported this year’s gun-control package. (A representative for the recall efforts did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this article.)

Meanwhile, the chill around federal gun-violence research might be thawing. Last January, among his 23 executive orders regarding gun safety in the wake of Sandy Hook, President Obama issued a directive for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assess the health risks and precautionary opportunities surrounding firearm violence. For the first time in 17 years, federal researchers could legally, openly evaluate guns as a public health threat. That study’s findings, released in June, illuminated the complicated tangle of facts around guns in America—facts that both sides of the gun-control fight have co-opted to discredit the other. For instance, gun violence nationwide has largely stabilized or declined over the last 20 years. Gun-rights supporters point out the finding that guns are used frequently and effectively for self-defense, thus negating the need for any new firearms prohibitions. Gun opponents, on the other hand, attribute the declines to the increased oversight that followed in the wake of the Roberti-Roos Act, the expired national assault weapons ban and other legislation.

A recent publication by the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence spotlights this plunge in California in particular, where gun deaths dropped 56 percent between 1993 and 2010. But the inconsistency of laws state-to-state means that any gun that’s forbidden in California might be perfectly legal just over the border in Nevada, Arizona or Oregon—in the latter of which Purdy bought his AK-47

in 1988 and whose current laws would permit him to buy the same type of gun today, provided that it was manufactured in the United States. Now, as then, no law passed in Sacramento can stop a gun bought outside the porous state lines from entering California. Indeed, no state imports more guns used in crimes than California—nearly 4,500 guns in 2009 alone, according to a study published by the advocacy group Mayors Against Illegal Guns.

Moreover, says Rob Young, gun opponents’ focus on things like magazine capacity or firearm design overlooks the even more crucial issue of mental health. “We put someone on a psychiatric hold, and it’s like a turnstile,” explains Young, citing one of his chief frustrations as a police officer. “They’re out before their report’s done. Some of these people are really sick, you know? Patrick Purdy—I mean, how many times did he slip through the system? They need to focus more on that, and paying more attention and pouring more money into this rather than saying, ‘We’re going to fight this and ban firearms and make it harder for people to own guns,’ which is going to do nothing.”

Former legislator and gun-control pioneer Mike Roos agrees with Young—to a point.

“I’m not a believer that there’s a simplistic, one-answer solution,” Roos says. “It’s a series of complexities, and the more that we see on the national scene, we realize that mental health is clearly a part of it. What we tried to do is basically just stem the availability to at least have some hurdles and to take some guns that were just wholly inappropriate for anyone being able to walk [into a gun store], and in five minutes walk out armed as if they were a member of the Secret Service. I believe that the more we can research, the better or higher ground that policy makers are able to stand on.”

To that end, the National Institutes of Health have called for grant proposals this winter to study the intersection of violence and firearms. Among the participating institutes are agencies specializing in mental health, drug and alcohol abuse, children’s health and women’s health. The dollar amounts of the grants aren’t yet specified, but the opening date for two of them is Jan. 16, 2014— one day before the 25th anniversary of the Cleveland Elementary School shooting. It’s a momentous bit of outreach in the fraught climate around gun rights—one not lost on Wintemute, who effused with encouragement on the day the grants were announced.

“Doing research isn’t promoting gun control,” he says. “Maybe what you do with the findings could be seen as [that], but the research isn’t. So what the President did in January was to make precisely that point.”

Still, there is that searing question: “What next?”

Stockton knows the answer, as sure as the January sun burns off the valley fog over Cleveland School and the kids run through this and every quietly stricken campus that followed it. Stockton knows the rancor and recriminations that flowed north to Sacramento. It knows the lessons and rites that have begun in Newtown—the lists, the portraits, the anniversaries. The mornings after, the public outcry of days, the private mourning of decades.

Stockton knows where to turn. “It’s very important to talk about the incident—to talk about how you’re feeling, to let your emotions out,” says Khorn Ing, the victim’s mother. “Because if you hold it inside, it’s going to build up inside and explode like a volcano.”

It knows the rage and fear.

“What’s scary to us is we know it’s going to happen again,” says Julie Schardt, the teacher. “And people are going to get upset again, and they’re going to tear their hair out, and they’re going to say, ‘Why haven’t we done something?’ We know it’s going to happen again. And it’s going to be a school, and it’s going to be somebody’s kids.”

It knows the caution.

“We have to look back to other children that we have,” says Sovanna Koeurt, the leader, who urges parents, teachers and peers to preempt violence through vigilance and love. “We have to look to them more closely; maybe before we ignored things. And now we take care of them very well. Maybe you change a little bit. You work with them; you think about them more.”

It knows the reflection.

“Parents lost their children that day, and brothers and sisters lost their siblings,” says Rob Young, the victim who now enforces the law. “It’s sad. And as a parent, God forbid anything happened to my kids, I’d want people to remember them. It’s not about rehashing bad memories. It is a bad memory, but I think something can be learned from it, too.”

And it knows the resolution.

“This problem is big, and it’s absolutely not acceptable, and we as a country are going to do something about it,” says Wintemute, the doctor. His voice is forceful and lean, stripped of everything but purpose. “And maybe it’ll take us five years, maybe it’ll take us a generation. Don’t care. We’re going to do it.”