The Sins of My Father

As a Yolo County organic walnut farmer and a longtime leader in California agriculture, Craig McNamara—pictured at below as a teenager in the White House in 1968—has devoted his career to practicing sustainable farming, feeding the hungry, and growing the next generation of farmers as the founder of the highly acclaimed Center for Land-Based Learning. But in his new memoir Because Our Fathers Lied, excerpted below, he recounts his deeply complicated and conflicted relationship with his father, Robert McNamara—the chief architect of the Vietnam War and one of the most controversial political figures in American history.

If any question why we died

Tell them, because our fathers lied

—Rudyard Kipling

Just tell me the truth. Seems simple enough. Yet for all of my life, I struggled to arrive at the truth with my father. He never told me that he knew the Vietnam War wasn’t winnable. But he did know, and he never admitted it to me. More than a decade after his death, I still wonder why he was no more honest with me than he was with the American public.

When I was a kid, my parents were infallible, like two gods. My life revolved around my mother and father: the peace of our family, the security of my school, friends, and home. We lived in Washington, DC, among the rest of America’s sometime deities, those who in 1964 still remained from Camelot.

I remember the familiar arched hallway of our three-story house. We had huge double doors at the entrance. Our hallway mirror reflected my mom’s stairway planter, as lush as an indoor greenhouse. Coming home from school each day, I’d search for a snack in the faded yellow kitchen. I never had to wait long for my mother’s embrace. My dog Michael, a golden retriever, was always present. In the evenings and on the weekends, my parents and I would walk beneath the elms and flowering dogwoods of Rock Creek Park. These were brisk walks. Nothing slowed my dad down, neither the scent of the azaleas nor the ephemeral sense that we were at peace.

The author at his organic farm in Winters in January 2022 (Portrait by Malika Lewis, courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

On Sunday mornings, two or three newspapers arrived at our front door. I would retrieve them and bring them into the kitchen. Dad would unfold the newspapers on the dining room table and read them from cover to cover, with a furrowed brow and clenched jaw and with his blue china coffee cup poised in his left hand. I could hear Mom scrambling eggs with her wire whisk, roasting bacon, and toasting Dad’s favorite whole wheat Thomas’ English Muffins. My role was to sit quietly at the table.

I don’t think it was mere silence that my father required at breakfast. Rather, it was a moment of peace in what must have been days of striving, a hurried and demanding life. Invariably on those quiet Sunday mornings, the kitchen phone would ring. My dad would answer, and after clearing his throat with a short cough, the first words out of his mouth would be “Yes, Mr. President.”

Pause.

“Well, Marg was planning on making cheeseburgers for Craigie and me, and maybe some tennis in the afternoon.”

Another pause. I couldn’t hear what President Johnson was saying on the other end of the line, but I could hear his voice in my head. That familiar drawl was not yet threatening. A smile formed on my lips.

“Oh, yes, Mr. President. We’ll be there.”

Shortly after the call, we all got into the blue Ford Galaxy with DC license plates (#3) and drove through the empty avenues of Washington to the White House. There wasn’t much traffic in those days, and the drive wasn’t long. This trip happened several times, but I never got used to it.

The guard at the entry gate leading into the Rose Garden raised the iron post as we arrived. We drove up to the White House, where the President was waiting to greet us. With his sweet Texan demeanor, Lyndon Johnson leaned over to my mom, gave her a big kiss, and said, “Margy, it’s so nice to have you and Bob come by. Bring that boy of yours up to our family dining room, as I know he must be starving.”

✦

In the dining room, President Johnson sat at one end of a deeply polished mahogany table, with Lady Bird at the other end. The ceilings were high, the walls painted with murals of colonial scenes. The room was both grand and intimate—warm but also echoing and exposed. Dad was seated to the President’s left, Mom to his right. To this day, I can’t remember where I sat. Perhaps these experiences were too overwhelming for me to form memories. I do remember that the President was always gracious and generous.

After lunch, the President suggested that we take a dip in the indoor pool. What he really meant was that I was to take a dip while he and my father discussed the escalating war. I changed into my suit and jumped in. I kept my head above the surface, treading water in the deep end and thinking all the time about how a young American man ought to look, what face he should make. Above me, the ceiling was all blue skies and puffy clouds—painted on, peace distilled beneath the roof. From the far end of the pool, I could see the President and his loyal secretary of defense hunched over a coffee table stacked high with briefing papers. Now and then a few words reached me, the tone of a man’s voice above the lapping water, but I didn’t know what they were saying.

I can imagine it was fraught. The President had called his closest adviser on a Sunday morning to support him in what must have been a lonely and torturous time in the White House. The war was ramping up. What were they planning? What disastrous paths were they debating as their wives chatted comfortably nearby?

Floating in the White House pool, I had a sense that I was included in something important. I always hoped for a family day on the weekends, always wanted to go on a walk with my mom and dad, maybe play tennis, but a trip to the White House was incredibly exciting. These were strange and magical experiences for a thirteen-year-old kid. With my two older sisters already off to college and adult life, it was just me and my parents. Visiting the White House, I felt special.

The day after our lunch and swim, I sent the President and Mrs. Johnson a handwritten thank-you note. Just a few days later, I received a letter back from President Johnson. For a man about to drag a nation into war, he was quite prompt in his replies. The final line of his letter read, “You were cheerful to be around.”

That pretty well sums up how I thought I could and should support my father in those days. I swam near him, never went too far from his waters, and put on the right face. All thoughts of the war hovered somewhere between my head and the ceiling. I was unaware of what was coming.

OUR SONS ARE DYING

The year I started boarding school, Norman Morrison stood beneath Dad’s office window at the Pentagon, doused himself in kerosene, and self-immolated. His infant daughter, Emily, by his side.

Paul Hendrickson, who would go on to write meticulously and gracefully about my father’s psyche, described Norman’s death in an article in The Washington Post:

He did it one rush-hour evening, in gathering dark, 40 feet below the window of the secretary of defense. The flame shot 12 feet in the air, making an envelope of color around his incinerating body. The sound of it, they said, was like the whoosh of small rocket fire. …

The public burning of Norman Morrison occurred in the gathering dark of a mistaken Asian war that Lyndon Johnson and all his steadfast men had lately, and mostly by stealth, made incendiary and even more mistaken. That summer, Vietnam had suddenly become a huge conflict, no longer the nice little one-column firefight everybody thought it was going to be a few years earlier. There seemed to be no exit from the chosen path; 175,000 men were going in. American bombers had been raining destruction on the North since the previous February. …

In the South, Buddhist monks had been immolating themselves for two years, but this burning seemed vastly different. It had occurred in our own civilization, right “at the cruel edge of your five-faced cathedral of violence.” Those were a poet’s words a few days afterward, and the poet must have had more in mind than the Pentagon itself. (Seven days later, a 22-year-old Catholic named Roger LaPorte would set himself afire at sunrise in front of the United Nations.) In the weeks and months following, there would be hundreds of poems pouring forth. It was as if only the poets could understand this thing Norman Morrison had made with his life. One poem was titled “Emily, My Child” and was written by a man named To Huu, one of the most famous poets in Vietnam. Another, addressing Defense head Robert S. McNamara, who was inside the five-faced cathedral that afternoon, began: “Mr. Secretary, you were looking another way / When grief stalked to your window to forgive you.”

My office is a simple shed on my farm in Winters, California. When I sit at my desk, I look out my window at acres of walnut orchards. A few feet away from me, mostly unused, is Dad’s rolling chair from the Pentagon. I can imagine Dad sitting in this chair when Norman burned himself alive. I picture Dad viewing that unfolding tragedy from his office, the most quotidian of settings, a place that in seven years I visited fewer than a handful of times. I can imagine his horror at witnessing a human life extinguished before his eyes. But the truth is that I don’t even know if he looked. I have heard that he did; I’m not quite sure from whom, probably Paul Hendrickson. I didn’t hear it from my father. He never said the name Norman Morrison to me, ever.

I was fifteen on November 2, 1965. I had arrived at St. Paul’s School two months before Norman’s death. At that time, I was attempting to adjust to the rigors and demands of my new environment. On that Tuesday evening, I suppose I was walking in the autumn twilight from my dorm to the dining hall. It would have been getting cold. I would have seen my breath in the light of the lamps around the grounds, the chapel, and the school-house. I was passing through a dream of America’s making, while a nightmare of my father’s making unfolded many miles down the Eastern Seaboard.

Like so much about my father’s life, I’ve had to understand this tragedy by reading other people’s words—the words of journalists, historians, and essayists. It’s very possible that the first time I ever heard about Norman Morrison was in 1985, when I read Paul Hendrickson’s article in the Post.

I cried after reading about Norman—cried for the loss of that life, and for the loss of others represented by the act. For months afterward, the very breaths I took felt selfish. I felt ashamed to be alive. Today, having had many decades to process the emotions, I cry knowing that my shame and grief must have affected my family. Norman’s daughter, Emily, was an infant at the time of his death. Many years later, my wife and I named our daughter Emily. Did I ever think about this connection?

Dad never talked to me about the time when a disgruntled protester tried to throw him off a Martha’s Vineyard ferry. I found out about that on my own, again through reading. The absence of my real dad, and the overwhelming presence of so much historical material about him, make me imagine certain scenes from his life like moments from a play or movie. I am the director of my own fictional scenes, projecting a world. Had I been home in Washington after Norman’s death, I imagine I would have witnessed a ghostlike version of Dad, with hunched shoulders and a pale face, bringing darkness with him through the heavy hickory doors of our home. Maybe his voice would have wavered while his left hand rubbed the tears from his eyes, dramatically, so that we, his audience, would know what he was feeling. Would I have hugged him, gently saying, It’s not your fault?

What if Norman and Bob McNamara had actually met that day? Could Norman have persuaded my father to make different choices? Could the secretary of defense have dissuaded Norman from self-immolating? Would Dad have called me at boarding school, to tell me what happened?

All speculation.

✦

One way or another, things pass through generations. Yet I can’t remember one time when Dad spoke to me about his father, who died when Dad was in his late teens or early twenties. I didn’t have a grandpa growing up, and I don’t have many memories of my grandma either. I faintly remember her staying with us in Ann Arbor when I was six or seven years old. I recall an incident when I said something inappropriate in front of her, and she hauled me up to the tiled bathroom of our two-story Tudor home to wash my mouth out with soap. I often wonder if she treated my father this harshly. I don’t think that Dad even attended her funeral. What kind of childhood brutalities did she inflict on him?

Books about my father fill in my family history, which should have been the task of the family itself. I should have heard from Dad about his upbringing during the Depression; I shouldn’t have had to learn about it through second- and third-hand sources. At times, when I try to read books that go into our family history, I feel an emptiness spreading from my center. Parts of my body feel as though they’re shutting down.

In certain writings and interviews, especially later in his life, my father stated that it was his intent to keep his family life separate from his career. He always tried to shield us. To an extent he succeeded in keeping his work as a statesman hidden. Even as a teenager, I never felt that I understood his daily routine or what his work consisted of. In fact, I didn’t know the simplest things about his job—what motivated him to do it, and what aspects of his daily duties he enjoyed.

But try as he might, he couldn’t always prevent the intrusion of reality. Etched in my memory is a series of eerie moments when the Bob McNamara shield cracked. I remember a ski trip to Aspen when I was in my early teens. It was Christmas vacation. After a day on the slopes, my parents’ friends gathered in the ski lodge. They sipped cups of spiced tea and hot chocolate. A fire was blazing in the corner, drying our wet gloves and caps. One couple in the group were Quakers. They had assembled a seminar on the Vietnam War. They were dead set against the war, and they stood before the group, my parents included, and spoke with compassion about the need to end this violence. I don’t remember my father’s response. However, I do have a memory of the expression on his face. He looked like a condemned man.

After the conversation, we all made our separate ways back to cabins and lodges, built little fires and turned the lights out before bed. I wanted Dad to acknowledge what happened. I wanted him to say to me, “Craigie, it will be all right.” But he acted as if nothing had happened. Our lives resumed, and he continued to bury himself in the morning New York Times and Washington Post.

In those days, I didn’t feel blame and resentment yet. Only grief. The controversy and tragedy in America during the mid-1960s suffocated us with grief just as much as they did the rest of the country. In my father’s face and walk, even in his silence, I began to see flitting shadows of sadness. I didn’t know it as a boy, but these were signs of depression, for which he would seek treatment later in life. It was during this time that my mother and I began to develop ulcers.

For most of my life I have attributed my ulcers to extreme stress. As a kid, school was my greatest source of stress. I remember crying uncontrollably over my homework, going back to at least the fifth grade. By the time I entered ninth grade, I had started to notice a biting, acidic feeling in my gut whenever I tried to struggle through any assignment based on reading or memorization. At boarding school, playing so many sports, I came to see my stomach pains as a point of honor, something to be endured in a manly way. I would grimace through them on the practice field. Riding in the front of the team bus, hyperfocused and competitive, I nearly forgot that I was hurting. Invariably, I would be clutching my stomach after the game was over, feeling that burn during the ride home.

In the mid-’60s, my mother and I went to see a Dr. Tumulty at Johns Hopkins. She and I had the same symptoms, and we were both diagnosed with ulcers. I assume we shared a genetic predisposition. More, I think that we both felt the weight of my father’s decisions throughout our bodies and in every part of our minds. With a penchant for optimism, we never expressed our anguish in harsh words or self-abuse. Nor did we direct it at Dad. It all expressed itself in a more internal way. Dr. Tumulty advised us to drink more milk, and he prescribed a few drugs that didn’t have much effect. I continued to feel pain from my ulcers well into college, where they sometimes had me doubled over as I walked from my dorm room to a class.

Dad must have known that we were suffering—especially Mom—throughout his time as secretary of defense. It must have worsened the pressures of his office. I imagine that every long working day and every difficult decision about Vietnam felt like an act combining courage, drudgery, and treason. The mere fact that he kept himself going during this time, that he didn’t collapse in a hallway or pass out at his desk, is remarkable and disturbing. It takes a person with a certain misplaced strength to continue along a path that causes suffering and destroys lives—to know the costs and to continue all the same.

✦

Dad left Defense in February of 1968. Depending on your interpretation of history, he either resigned or was fired, or a combination of both. I was approaching the end of boarding school, in a transition away from that repressive environment. It seemed that our family was coming to a new beginning.

On February 28, Dad was set to receive the Medal of Freedom from President Johnson in the East Room of the White House. I remember the whole ceremony as an almost religious experience; the light was coming in through the windows, pushing the dark out. At last we would be free from the war. Or so it seemed.

In a picture from that day, Dad holds the presentation box containing the medal. Over his left shoulder, my mother peers into the box, my oldest sister, Margy, at her side, my other sister, Kathleen, next to her. I am half out of the frame, the youngest kid by nine years and last in line, clapping my hands after the President concluded his remarks.

It was emotional for me to hear the President honor my father, and it must have been equally emotional for my sisters. LBJ and Lady Bird had attended Margy’s wedding in 1965. I remembered the President’s calm demeanor in the foyer of our home, socializing with wedding guests. Dad himself had given the commencement address at Kathleen’s graduation from Chatham University, a then-all-women’s college in Pennsylvania, as anti-war protesters demonstrated in front of the hall with signs that said “Bring our boys home so we can marry them.”

Throughout our lives, my sisters and I have never talked about the ceremony in the East Room. In the picture, we look a bit like startled deer, unable to find our way back to some familiar pasture. If we could have gone there, to a quiet place of peace, we might have asked each other, How are we going to live, knowing what our dad has done? No such conversation ever took place, and that absence is a residual example of the pattern Dad had established with me: to go forth in life with a singular purpose, work hard, and shield family members from your innermost feelings.

However we all felt, the ceremony was certainly the most emotional for him. As Dad rose to receive the medal and make his speech, he broke down, unable to control his emotions. He coughed so that he wouldn’t cry. In the shortest of moments, he stepped off the podium and into a new phase of his life.

Craig McNamara (third from right) with his family and President Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson at the White House in 1968 on the day that his father, Robert McNamara, was awarded the Medal of Freedom (Courtesy of Craig McNamara)

In my family archives, I discovered a copy of a letter from Dad to President Johnson, dated just a few days before the ceremony. I believe that in this letter, Dad expresses some version of what he intended to say upon receiving the Medal of Freedom. The letter begins in true Bob McNamara style: “Fifty-one months ago you asked me to serve in your cabinet.” Not “fifty months ago.” Not “four years ago.” Fifty-one.

The letter then takes a deep dive:

No other period in my life has brought so much struggle—or so much satisfaction. The struggle would have been infinitely greater and the satisfaction immeasurably less if I had not received your full support every step of the way.

No man could fail to be proud of service in an administration which has recorded the progress yours has in the fields of civil rights, health, and education. One hundred years of neglect cannot be overcome overnight. You have pushed, dragged, and cajoled the nation into basic reforms from which my children and my children’s children will benefit for decades to come. I know the price you have paid, both personally and politically. Every citizen of our land is in your debt.

I will not say goodbye—you know you have but to call and I will respond.

I’m amazed by the humility in these lines, which is to a fault. Dad’s attempts at sincerity pushed him far from his own voice. When he uses words like pushed, dragged, and cajoled, I feel as if I’m reading someone else’s prose. These sorts of words were unusual for my father. To me, they’re earthy words. I find them closer to references I would use on my farm.

My father writes of how President Johnson’s accomplishments will matter for his “children’s children.” It’s the sort of stock phrase that politicians and public figures use. I’m sure that these words don’t stand out to many people who read In Retrospect, the memoir in which Dad quotes this letter in its entirety. But they stand out to me. Because his children’s children are my children.

My wife, Julie, and I purchased our farm in 1980. Dad died in 2009, and I can count on one hand the number of times he came and stayed with us on the farm. As a result, he barely got to know my kids. He held them in his arms only a few times. They’re not just his children’s children. They’re Graham, Sean, and Emily.

READ MORE: A Winters Tale – Craig McNamara and Nurturing the Next Generation of Farmers

When my dad writes that he was not duplicitous to the American people, I think he’s ignoring a different truth. He was duplicitous to himself. Maybe the pressures of his office had required him to be absent from our lives, and to be dishonest about what was really happening in Vietnam. But why couldn’t he make himself more present and honest once he left office?

The journey we began as a family that February, which could have been a journey to understanding one another in a life of peace, was never properly begun.

There were many conversations I didn’t have with my father about Vietnam. There is one that I did have. After he published In Retrospect in 1995, I went to visit him in Washington. Dad was still living in the house where I grew up: 2412 Tracy Place NW.

After dinner we began chatting over drinks in what he called the “Green Room,” which was his study. We talked about the enormous blowback caused by his memoir. I hadn’t read it—at that time, I hadn’t read the vast majority of my father’s writings—but I understood from media coverage that his latest book, the first in which he truly addressed his controversial role in Vietnam, had not garnered the reception he had hoped for. Although Dad felt that he had admitted his mistakes, veterans who reviewed the book thought he stopped short of apologizing. In the pages of The Washington Post, Ron Kovic (author of Born on the Fourth of July) had written passionately about wanting Robert McNamara to understand the true cost of the war, which could not be calculated in lessons learned but in lost limbs and lives.

Ron lived in California. After his review was published, I called him and spoke with him. I wanted to feel fully his justified anger. I wanted to know the pain that veterans were feeling. Speaking with Ron, I understood that he wanted to welcome my father into the community of people who could understand, acknowledge, and feel the irreparable harm of the war—people who were wounded. So why wouldn’t Dad have that conversation? Why wouldn’t he meet with someone like Ron? This was a duty he owed veterans.

Dad and I went on a walk around the neighborhood. The conversation changed. It had been about the book; now it was becoming about us. I had an aggressive posture that evening, and I was more demanding than I’d ever been. We kept our voices down—this was an elite DC neighborhood, after all—but I was still brutally honest with him.

“I guess they’re mad because it took you thirty years, Dad.”

His views on this never changed. “You have to remember, I was acting from my experience in history.”

“And you still acted wrong.”

These were the most probing things I ever said to him. My words were heartfelt, not strategic. Later in life, when I desperately wanted to have a more complete conversation about Vietnam, I think Dad could sense this in me, and he was better able to deflect the subject.

At one point I asked him, “Dad, why did it take you so long?” What he said still causes me to pause.

“Loyalty.”

I might have said to him, Why can’t you be loyal to me, Dad? Or to yourself? What about the people who died? What about that loyalty?

I never asked him that first question, about loyalty to me, but I wish I had. That night I was trying to get him to say I’m sorry for Vietnam. I believed he should have apologized more fully. But Dad couldn’t do it. He ended the conversation by talking about himself in a vaguely repentant but unapologetic way.

“I made mistakes, Craigie.”

Loyalty, for him, surpassed good judgment. It might have surpassed any other moral principle. Dad was loyal to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, and that loyalty had many consequences. He came to be personally identified with the Vietnam War. At times I thought this was unfair. Out of a desire to defend him, I sometimes made excuses. He was just one of many people responsible; he was underqualified for the job; his business background and statistical fluency made him a perfect symbol for the hated military-industrial complex, the great machine. It wasn’t all his fault.

But he didn’t speak up enough when he knew the war couldn’t be won. While in office, he repeatedly told the public that we were making progress in Vietnam—that victory was just around the corner. For years afterward, he deflected questions about his Vietnam leadership, undermining the truth by refusing to take responsibility for policies that had horrific consequences. Whether it was the use of Agent Orange, the bombing campaigns that killed millions of civilians, or the faulty statistics he relied on, Dad didn’t admit to his mistakes when doing so could have changed history. He always hid behind simplistic words like those from his memoir—we were wrong, we made mistakes.

His loyalty was a kind of corporate loyalty. Regardless of the consequences for ordinary people, Dad stayed loyal to the system. He may have believed that he was only part of the system that caused the war, but he was still one of the nation’s most prominent leaders, one of the few with the capacity to reshape policy with his leadership and intellect. If he thought the war was wrong but couldn’t buck the system, then he should have left that system. He did not. Instead, he waged war. Afterward, he didn’t say he was sorry. To me, this is the truth about his loyalty.

✦

Meanwhile, Dad’s loyalty provided him with many personal advantages. After his departure from Defense, he stepped into a career as head of the World Bank. He spent the next twelve years visiting practically every country and prime minister in the world. A global dignitary, he never had to suffer the consequences of losing a war. In other countries, countries that aren’t the American Empire, the losers of wars are executed or exiled or imprisoned. Not so for Robert McNamara.

After my mom died in 1981, the boards of Dutch Shell Oil, Bank of America, The Washington Post, and the Rockefeller Foundation wined and dined Dad, flying him all over the world to consult on the cutting issues of the time. His confidants were Jackie Kennedy, Kay Graham, Ted Kennedy, and President Bill Clinton. The firm Corning Glass gave him a handsome corner office in Washington, where he had a magnificent glass globe. Each and every one of his friends, in and out of government, appreciated his loyalty to them. Though he never bragged about his captainship of global intelligentsia and trade, I know that he liked it. He often told me how much he enjoyed flying from Boston to London to attend meetings, because he could see Martha’s Vineyard out the window of the plane.

Did I benefit from Dad’s loyalty? In many ways I did. On climbing trips, we were literally tethered to the same rope as we ascended Mt. Rainier or rappelled down the face of Grand Teton. Yes, he was loyal.

And I have been loyal to him. In his final months and days, I bathed him and dressed him. I have sometimes worried that I treated him too generously, especially in interviews and in writing, handling him with kid gloves. It’s hard to be objective. Goddammit, this is my father we’re talking about: caretaker, loving dad, hiking buddy—obfuscator, neglectful parent, warmonger.

✦

In February of 1968, the month of Dad’s retirement from Defense, my St. Paul’s classmate Cam Kerry wrote an op-ed in our school newspaper, The Pelican.

We are trying to win the unwinnable war, like Don Quixote, “to dream the impossible dream,” and like Don Quixote, we are doomed to tilt at windmills.

At the time he penned this op-ed, Cam was only seventeen years old. His brother John Kerry was commanding a Swift Boat in Vietnam.

The clarity of Cam’s conviction amazes me today. When I was at boarding school, I didn’t realize how politicized and informed many of my peers were about the war. Cam managed to express himself in such certain and powerful terms in a public forum. At around this same time, I stood in the East Room of the White House meekly, watching my dad receive the Medal of Freedom, feeling a mixture of pride, embarrassment, amazement, and discomfort, with uncertainty as to the proportion of each emotion.

Where was the op-ed that I might have written? At that point I still couldn’t string sentences together for a term paper. Instead, I was on page seven of the March 12, 1968, edition of The Pelican in a story about sports. “McNamara Wins in School Wrestling Tourney.” I wasn’t even on the wrestling team. There had been an open tournament, and I gave it a go, channeling my energies toward these light competitions while some of my peers were trying to make themselves heard.

I didn’t express myself at boarding school, but in my bedroom at home during the summers, where my father might see them, I began my earliest protests. On the third floor of our home on Tracy Place, I hung the American flag upside down on the wall above my bed. After that, I stamped my letters with the upside-down American flag. I imagined the mail carrier looking at the outside of my letters and knowing that someone in the McNamara house wasn’t for the war.

These were vulnerable years for me as the youngest child in the family. I experienced that unique window of time, uncomfortable and powerful in its intimacy, reserved for the last child remaining in the house. Even without the Vietnam War, this would have been a period of reshaping my relationship with my parents. It coincided with the beginnings of a national (and international) nightmare.

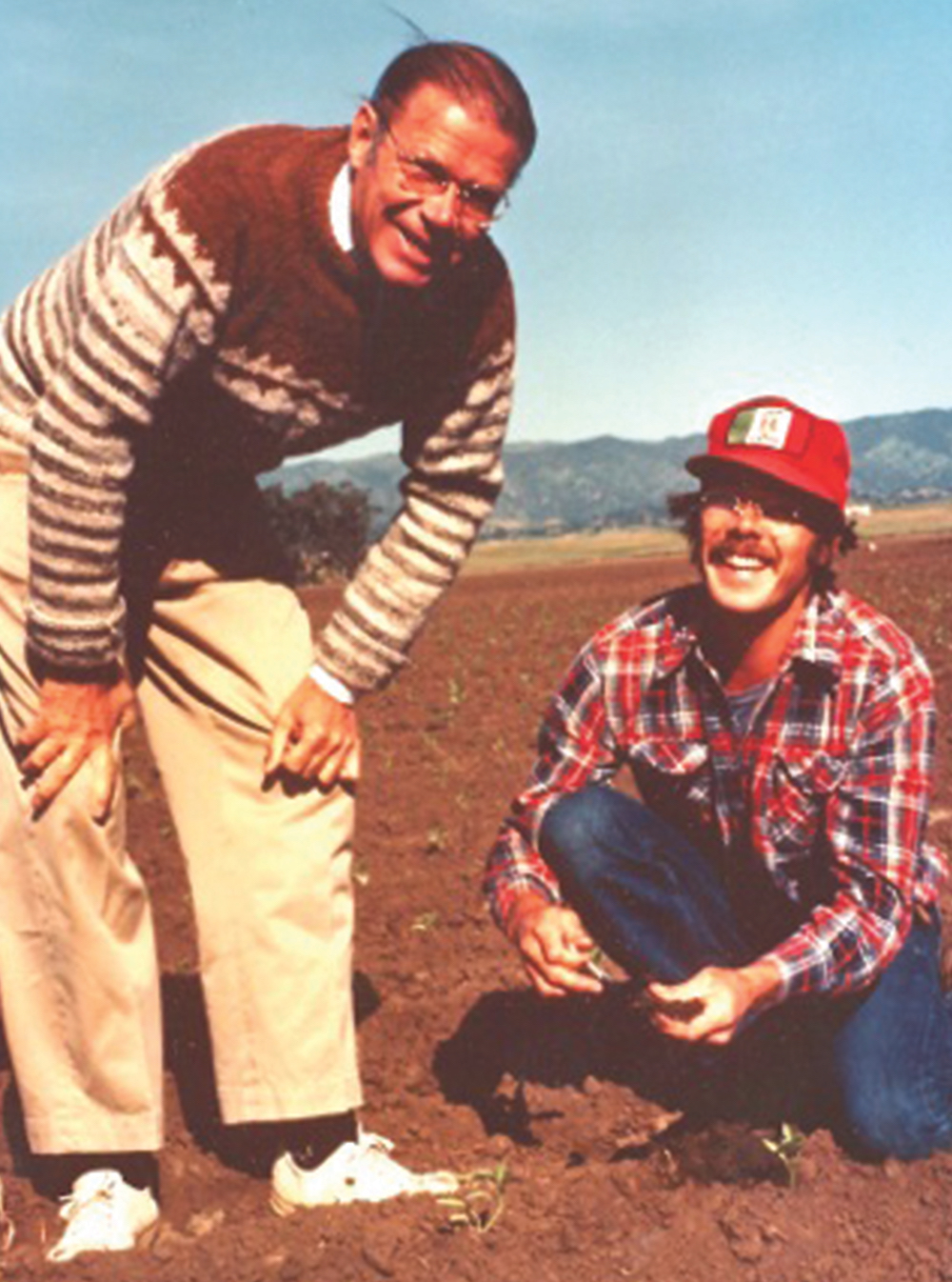

Craig and Robert McNamara at Craig’s first rented farm, near Winters, in 1978 (Courtesy of Craig McNamara)

Returning from Vietnam, Dad would bring home certain artifacts. These included rifles, pistols, flags, and other objects from the field of battle. They were not souvenirs, nor trophies; I think that Dad was interested in them as historical and cultural keepsakes. Throughout his life he collected objects from overseas, including during his travel as president of the World Bank. I soon developed a complex relationship with these Vietnam artifacts. Without telling him, I pilfered them from wherever he had deposited them (probably his closet or study), put them up in my bedroom, and made them a part of my living space. Viet Cong flags hung on my walls. One flag was captured from the battle of Dai Do. It had been taken from a firefight in which US forces and the North Vietnamese army slaughtered each other in rice fields. I also had a collection of confiscated guns and bullets. Punji stakes adorned my shelves. These bamboo stakes were as sharp as razors and barbed in two places. They were used by the Viet Cong as traps—dipped in human feces, then placed in camouflaged pits. The idea was not necessarily to kill the soldier but rather to cause a wound that required medical evacuation by helicopter.

The decorations on a teenage boy’s walls don’t hold any great secrets. As a younger teenager, fourteen or fifteen years old, I probably felt a fascination with foreign guns. Eventually, I started to recognize the horror of those weapons, and it matched the discomfort I felt about the war. When I was sixteen and seventeen and growing in my understanding, the Viet Cong flags came to represent a protest against my father. My response to the war may not have been an intellectual or an editorial one, but my feelings about the war were becoming stronger every day. My father never acknowledged what was going on in my bedroom. Certainly he never brought it up. My mother, on the other hand, tried to temper my protests, which must have been seen by Dad as painful insults. She often ascended the carpeted stairway to my room. In her gentle voice, Pacific-blue eyes shining, she’d ask me something about my life. Did I feel confident in my classes at school? How were my friends doing? Was the pain from my ulcers any less severe?

In response, I would try to deflect and comfort her. “How are you doing, Mom? I’m doing fine.”

I remember Mom pleading with me, “Just give your father another chance. Keep trying.”

She probably said something similar to Dad. “He’s just expressing himself. He’s saying how he feels.”

How can you open the door to someone who won’t walk through?

✦

This story of absence is the same story told about many fathers and sons. With my father, there’s also the question of evil.

There was an afternoon in 1979 when I went to the Tower Theatre in downtown Sacramento with Julie—my girlfriend and future wife—and my mother. At the time, we were renting a house in the countryside around Winters. Mom was staying with us. After some casual conversation, the three of us decided to have an evening at the movies. Apocalypse Now was playing.

It must have been late summer, shortly after the film premiered. I can’t remember if I thought about the consequences of taking Mom to see a Vietnam War film. I do remember that the hype around Apocalypse Now was significant. Perhaps I was the driving force for this. Maybe I thought it was a way for us to close out that chapter of our lives—to view a tragedy in the theater, to experience a catharsis.

I distinctly remember where we sat: midsection, about fifteen rows back, just under the vintage chandeliers. Mom sat between Julie and me. I don’t remember any tension in her posture. Then the room went dark. The soundtrack began, with Jim Morrison singing “The End.” Immediately I went deep into my own thoughts and feelings. The end of my mother’s life was not far away; she would die from cancer in 1981. The war had ended six years before, and my father’s tenure in government had also ended. Thoughts of so many endings overwhelmed me when I heard that song, and I felt myself losing breath, my chest tightening, like the feeling just before a sob is released. Only there was no release. As the movie played, and the violence mounted, I realized that this wasn’t an ending at all. The Vietnam War would continue to have profound implications for the country, my family, and me for years to come. We were just coming to the beginning—the beginning of the rest of our lives. There was a strongly felt, deeply personal sense of irony in hearing the words This is the end over the opening frames.

As we sat in the dark theater, I didn’t touch Mom. I glanced at her a few times to see her expression, and it was stoic. Crying was rare for her. She wore a coping face. I wonder what she was thinking about. I imagine she was horrified as we watched American helicopters rain down death and destruction during the Ride of the Valkyries scene. She and I are so similar, and we certainly are in this respect: we don’t like violence.

Taking my mother to the film was what Dad would have called “a god-awful mess.” More than that, it was a living nightmare. Why did I think it was a good idea? What could my mom have possibly gained from this experience besides despair and remorse? If she felt any relief that her husband’s active role in the war was over, perhaps that experience reopened an old wound for her. Maybe the ulcer in her gut writhed as the onscreen gunships spewed their bullets at innocent children. Did she mourn for the American dead, wondering if her own son should have served?

I honestly don’t remember what we did after the movie. I suppose we went out to eat, although it’s hard to imagine being hungry after watching Apocalypse Now. I’m sure that at some point, probably over dinner, I said, “Mom, I’m sorry.”

It would have been nice if my father had said these words. Again, that duty fell to me. And it was about a movie—an interpretation of his actions, far removed from him and from the victims of the actual war—not the real thing. I wonder if she told him about that night. I wonder if he was angry at me for taking her to the movie. I wonder if they even talked about it.

Recently I rewatched the trailer for the film. I immediately experienced the same dread I felt in 1979 when I sat next to my mom in the dark theater. At first I thought that I should watch the whole movie again, but after viewing several more trailers, I said to myself, Fuck, no. I don’t need to see any more representations of Vietnam War massacres. These fictional responses to my father’s war are inadequate to describe the magnitude of what he delivered to the world.

But what would be adequate? I think of all the unexploded ordnance in Vietnam, the lingering effects of chemical warfare, and I realize that the aftereffects will outlive not only my father but also me.

It’s not that I think he could have made up for his mistakes. What bothers me is that he didn’t make a sufficient effort. It took him decades just to admit that he made mistakes. Because of that fact, movies became one of the only ways for me to understand Vietnam with a degree of objectivity. As a noncombatant, I am limited in my understanding, informed by receiving literary and narrative interpretations. In that respect I am not unique; I share that experience with millions of other people. Yet I am unique in being the son of the war’s architect.

ABSENCE, DEFENSE

I remember, as early as age thirteen, having questions about my father’s integrity. He had numerous conflicts with members of Congress, and the press gobbled it up. An article from Newsweek published in March of 1963 describes his reputation:

With cold logic and a hot temper, Secretary McNamara took on congressmen last week in two fractious issues: the size and nature of the defense budget, and the huge (ultimately $6.5 billion) TFX aircraft contract. His opposition’s allies, barely behind the scenes, were the enemies McNamara has liberally made as a tough, head-knocking executive.

The article goes on to discuss the various things about Dad that bothered the pols: his arrogance, his condescending tone, and (most of all) his willingness to circumvent bureaucratic processes in order to get his own way.

At one point, my mother addressed this with me. I can’t pin-point the exact moment—which news story or national event prompted her to sit down and talk to me. I only remember that she came into my bedroom and explained that I might be hearing negative things about Dad. Later, during one of Dad’s congressional dustups, I spoke with a reporter. Again, it must have been my mother who allowed me to talk to the press. I would have sat in the living room on the phone, with Mom nearby or in the next room, listening in. When I spoke to the reporter, I asked, “How long will it take my father to prove that he’s honest?”

Soon after this quote appeared in print, I received a dozen letters from across the country. They vouched for my father’s character. Among them was a letter from Vermont congressman Robert Stafford, a former governor and future senator. On his official stationery he wrote, “I have had the privilege of observing your father for the last three years as he appeared before the House Armed Services Committee. I have come to hold tremendous admiration for his ability, judgment, and integrity. I think he is one of the ablest public servants with which this country has been blessed.”

Another letter, penned by a serviceman, read, “I wanted you to know that for me and for many thousands of other people, there is no question about your father’s honesty, or anything else about him. He is a great man doing great work. He is serving his country with a courage and devotion just like that of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln.”

Before I dug up that Newsweek article from March of 1963, I remembered having been quoted in it. This was not the case; my name didn’t appear. I must have spoken to a different reporter for a different article. What I remember more clearly, and very painfully, is finding out for the first time that my father was fallible, that his shield could be broken, and that he might not be the titan of my childhood. How could anyone attack his integrity? It must be a mistake. But then, how could he make a mistake? I was distraught.

It comforted me to know that a congressman, a member of the military, and private citizens viewed my father as a man of integrity. Getting those letters allowed me to consciously return to a state of innocence, where I could trust him. He would do the right thing. In retrospect, maybe it would have been better if those letters hadn’t come. Maybe it would have helped me to arrive earlier at the conclusion that my father’s life was not lived wholly on the righteous path. Maybe it would have saved me from the mind-bending pain of those years when I discovered I had been living in the shadow of dishonesty.

✦

Two decades later, in the spring of 1984, David Talbot wrote an article for Mother Jones, “And Now They Are Doves.” The article covered my father’s attempts to rehabilitate his image and step into the role of elder statesman. At that time, I was thirty-four years old, farming my heart out. I had a wife and child.

Over the years, I had thought about Dad every day with a mixture of love and rage. Whenever we spoke and I asked him about Vietnam, he deflected. There was never a big confrontation between us. I remember my life at that time as being defined by an absence of truth and honesty in our relationship, and I remember how I had defended Dad’s integrity when I was a boy—and the letters from his supporters too.

David Talbot called and suggested an interview, and it felt like an opportunity I needed to take. I didn’t want the media attention. I just wanted the chance to speak honestly, to be heard. David came to visit the farm in Winters, and we spoke for an afternoon. Earlier that day, I’d been on the phone with Dad, updating him on the progress of our orchards.

The published article in Mother Jones included a lengthy quote from me. I had never criticized my father so publicly.

There had to be a lot of guilt and depression inside my father about Vietnam. But he will not allow me into the personal side of his career. My father has a strong sense of what he will and won’t talk about with me. I would ask him things, like why he left the Pentagon in ’68. I felt I could learn a tremendous amount of history from him. And I felt I could teach him about the peace movement. But he just gives these quick 30-second responses, and then deflects the conversation by asking, “So how many tons did you produce on your farm last year?” Still seeking refuge in statistics.

I didn’t know if Dad would read the article. One of the many mysteries that remained was the extent to which he followed his own publicity. If I had taken the time to think about it carefully, I probably would have concluded that he did. After all, I knew of his ego and his need to be right, to win.

He called me up almost immediately after the piece ran. “Is that what you said?” he asked. “Was the quote correct?” I was a little surprised by the quick timing, but I wasn’t surprised by his response. If anything, it confirmed my disappointment in him. It showed that he cared about his own narrative, when he should have just driven himself hard to the unspun truth.

“Yeah, Dad,” I said. “The quote was correct.”

He was silent. This was always the way he reacted to being hurt. I knew I had hit him in a tender place. I felt sad, but I didn’t feel sorry. It was the first time I had offered my version of the truth and the first time he had heard it.

After a little time had passed, my stance softened. I reread the Mother Jones article several times and convinced myself that it was full of errors and omissions, and I started to believe that David Talbot had neglected important truths about my relationship with Dad—especially the fact, unavoidable, that we loved each other deeply.

I wanted Dad to know how I was feeling. In a follow-up letter to him, I wrote, “They failed to say that we have a relationship based on understanding.”

I really believed that, but it wasn’t the truth. Our relationship was, in fact, based on joy and affection when it came to the things we shared, and deliberate silence and absence relating to the issues of war and peace that divided us. If we had really had a relationship based on understanding, there’s no way I would have given that quote about his thirty-second responses.

As I reread the article today, I see that there were no errors. David Talbot didn’t misquote me or misrepresent my views. I was serious when I told him that I believed the power brokers in Washington, including my father, had made decisions in Vietnam based solely on the military interests of America. So why did I reverse course in private? I think I was reenacting the pattern Dad had established, the one I had learned to follow. I thought I could hold two truths in my head at once, in separate cages, without working through the dialectic. I love you, Dad, and I want you to love me. I’m angry at you, Dad, and I need you to hear me…

To be your son has meant many things to me. It means that there is a profound bond that exists between us that defies the differences that any two people naturally share. It means that you have shared with me part of your spirit, your vision, and your concern for our small planet and the billions of people that inhabit it. And it also means that we are two people who, with our individual and mutual skills and resources and knowledge, can help each other to achieve the happiness and satisfaction in our own lives that is essential to bringing it into the lives of others. We have so much to give to each other. Together we are a formidable team.

I feel the pain of the young husband and father who wrote those words. He was a first-generation farmer, with strong political ideals and a belief that the world could be changed at the level of the soil. He believed Robert McNamara was his partner in this.

There was an imbalance. My father was too silent on the most important subjects in our lives. In that letter, I think I let him win again. We could be father and son, we could be partners, we could be two men with the name McNamara. But we couldn’t really be a team. I know I’m yearning for something that might not have been possible. Wanting an unattainable thing leads to dark thoughts. It leads me to bitterness, to vehemence.

It may not have been so bad. It may just be that we lacked the depth of language and the emotional clarity to integrate the two compartments of our lives—love and strife—into a more holistic pattern. I doubt whether many fathers and sons arrive at such understanding.

✦

In letters to his friends, which I have in my farm office, my father sometimes refers to “Craig’s dream to save the world through farming.” He’s not wrong to call it that; yet I sense a certain sarcasm there that is hurtful. As a farmer, I’ve been hardworking, ambitious, and strategic. These were all qualities that Dad passed on to me, but I’m not sure what he ultimately thought about my career choices.

In “The Road Not Taken,” one of my father’s favorite poems by Robert Frost, Frost concludes:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

We chose different roads. I would like to think that I chose a more honest one. I know that I tried to bury a lot of guilt in the soil. Dad lived with guilt in silence, in a Washington office. The distance between our paths reflects an absence in our relationship. It was not just physical; the lack of honesty was even greater.

Then again, this poem is not really about the importance of the two paths. It’s about the folly of constructing neat narratives and explanations in retrospect.